Christmas with the Helmers

December 21, 2012

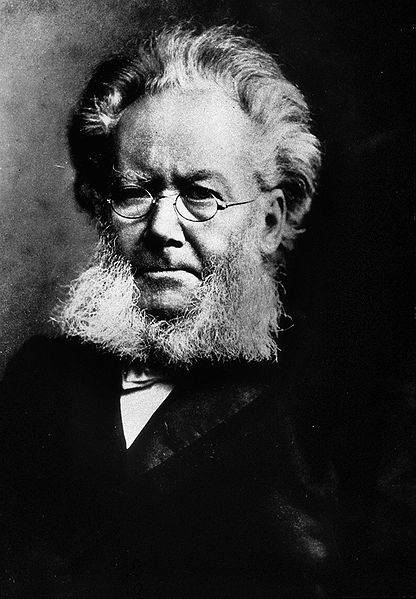

HENRIK IBSEN’S famous play A Doll’s House, which premiered in Copenhagen in 1879 and has been staged many thousands of times since, is a now classic statement of modern divorce. We will never know how many women have been inspired or encouraged to leave their husbands by Nora Helmer, Ibsen’s lovely and effervescent housewife who slams the door behind her when she leaves her home two days after Christmas, but we can assume that the immense popularity of this character in the ensuing years has had personal and grave consequences for some.

The play opens on Christmas Eve.

Nora Helmer returns to her comfortable and cozy Norwegian home after shopping for presents for her three children and her husband, Torvald. She is excited and happy. For the first time in years, she has felt free to spend at Christmastime. Her husband has a new job at a bank and, with this good fortune, they are likely to be comfortable for many years. Torvald is in the next room and soon comes out to greet her. He likes to tease her and call her his “little lark” and his “squirrel.” He finds his wife enchanting but also treats her like a child, a habit which she fully encourages. The moralistic Torvald is what people refer to today as a “control freak.” He even attempts to regulate what his wife eats. In contrast, Nora is sweet and charming.

The contentment of this Christmas Eve is soon shattered. Nora learns that an employee from the bank is preparing to blackmail them. Years before, Nora had, without her husband’s knowledge, taken out a loan from the employee, an attorney named Nils Krogstad. She had forged her father’s name on the loan papers because he was ill at the time and she did not want to alarm him. The reason for the loan was to afford a trip to Italy, a trip that was necessary to bring Torvald, who was also dangerously ill, back to health and that Torvald himself would not have approved of without the sudden gift of money from his father-in-law.

Krogstad intends to blackmail the Helmers because Torvald plans to fire him from the bank.

It isn’t until two days later, after a Christmas party at which the beautiful Nora has danced the tarantella, that the letter from Krogstad arrives, informing Torvald of his wife’s forgery. He immediately thinks the worst of his wife. From the Modern Language College translation by Eva Le Galliene of Six Plays by Henrik Ibsen:

“You’ve destroyed my happiness. You’ve ruined my whole future. It’s ghastly to think of!”

Torvald immediately tells his wife, before she has even explained why she forged the documents, that “there can be no further thought of happiness between us,” and that she will continue to live in the house but will have little contact with their children because she is unfit to raise them. He is a cruel prig.

His rage is cut short, however, when another letter comes from Krogstad. The lawyer, who has found sudden happiness with a woman, has changed his mind. He retracts his blackmail plan altogether.

But by now the damage has been done. And an immense change has come over Nora. In the 1973 movie version of the play, starring Claire Bloom and Anthony Hopkins, Nora, as played by Bloom, becomes almost robotic in her reactions. All expression drains from her face. She coldly states that her marriage is a sham and that Torvald is not the man she had thought he was. She had hoped that that he would refuse to be blackmailed and would stand by his wife.

What makes this a feminist play, despite the insistent disavowals by Ibsen that it was about women’s rights, is not that Nora then leaves her husband, slamming the door behind her. She was justified at that moment in being hurt, outraged and even in walking out, temporarily.

No, what makes it a feminist play is not that she walks out. It is the reasons why she does so — and the fact that she leaves him and her children permanently.

Nora is reasonable and she is just in stating that there is something fundamentally wrong in their marriage.

“During eight whole years, no — more than that — ever since the day we first met — we have never exchanged so much as one serious word about serious things,” she says. Their habit of playing roles — she the little bird and he the stern protector — hides a lack of connection and deeper rapport.

It is reasonable of her to point this out and demand change. Where she becomes unreasonable is in concluding that she cannot possibly be an individual in her own right as long as she is married. Torvald, and her father before her, controlled her thoughts and stifled her ability to think for herself.

“You and Father have done me a great wrong. You’ve prevented me from becoming a real person.”

Here we see the utopian basis of modern divorce. A “real person” is someone who can think and act entirely without the influence of others. A “real person” is thoroughly rational, arriving at an understanding of life entirely on his own. A “real person” is autonomous.

What Nora does not acknowledge in this now classic divorce scene is that once she is out in the world on her own, others will be preventing her from becoming a “real person” too. The people who employ her — for she has no money and will have to do some work for pay — will be impinging on her independence too. There is no such thing as the beautiful autonomy that modern divorce promises. Nor does Nora acknowledge that in her years of marriage, she has had many hours on her own, away from her husband, in which she could think. The real weakness in Nora is not that Torvald controls her thoughts, but that she possesses no inner independence. She has surrendered her mind and soul.

“I shall never get to know myself — I shall never learn to face reality — unless I stand alone. So I can’t stay with you any longer,” Nora tells Torvald.

A few minutes later, Torvald responds:

Helmer: “It’s inconceivable! Don’t you realize you’d be betraying your most sacred duty?

Nora: “What do you consider that to be?”

Helmer: “Your duty towards your husband and your children — I surely don’t have to tell you that!

Nora: I’ve another duty just as sacred.”

Helmer: “Nonsense! What duty do you mean?”

Nora: “My duty towards myself.”

In this moment, Nora’s cruelty to her children is breathtaking — a fact that was acknowledged by some viewers when the play first come out but is rarely, if ever, noted today.

Though Ibsen claimed he was not consciously working for women’s rights when he wrote the play, he also wrote, as quoted in Wikipedia’s entry on the play:

“A woman cannot be herself in modern society, [since it is] an exclusively male society, with laws made by men and with prosecutors and judges who assess feminine conduct from a masculine standpoint.”

It is not just marriage that has stifled Nora, but the whole edifice of male-dominated society which entails laws that do not allow a woman to forge documents if necessary to protect others. Nora says,

“I’ve discovered that the law, for instance, is quite different from what I had imagined; but I find it hard to believe it can be right.”

Ibsen’s play is about more than marriage. It is an argument for moral relativism and feminine power. Nora leaves not just to find herself, but to seek a new society.

— Comments —-

Thomas F. Bertonneau writes:

Ibsen is one of the most slippery characters in early modern literature. The best introduction to him comes from Paul Johnson’s book Intellectuals. Johnson, in a dedicated chapter, describes Ibsen’s egomania, selfishness, indulgence, lifelong bad manners, and relentless hostility to the social class that produced and permitted and latterly celebrated him, the bourgeoisie. Despite that, and on the whole, and without taking exception to your lucid analysis of the Torvald-and-Nora scenario, I find the Norwegian playwright worthy of study. I warm particularly to the work of his early maturity, especially to the plays Brand (1865), the last of his verse-dramas, and Emperor and Galilean (1868), the first of his outstanding non-verse dramas.

The two plays are closely related in thematics, both being about what modern conservatives, taking the lesson from Eric Voegelin, have learned to call Gnosticism. Brand, the eponymous central figure of the verse-drama, is a priest vaguely Christian but also so terribly more Christian than anyone else that everyone close to him becomes a sacrifice to his righteousness. The “Emperor” of Emperor and Galilean is the famous apostate Caesar Julian, who attempted to disestablish the religion (Christianity) that his uncle, Constantine I, had made the official religion of the Roman Empire. Now one might think, without having read the play, that Ibsen would take sides with Julian in the play. It turns out not to be so. Ibsen certainly sympathizes with his protagonist, but he also ruthlessly dissects him. Ibsen’s Julian, like Ibsen’s Brand, is a thorough Gnostic, complete with bizarre anti-Christian initiations under the mage Maximus of Ephesus in Part I of the play. By the end of Part II, Julian has become the victim of his own unreal delusions. The “Galilean” has won the field, so to speak, and the play implies that this is because Christianity is more deeply rooted in reality than Julian’s neopagan mysticism. That Ibsen’s Julian is also a social utopian makes the play even more interesting and more poignant from a modern, traditionalist-conservative point of view. Significantly, the last line of Ibsen’s last play, When We Dead Awaken (1899) echoes the finale of Emperor and Galilean, announcing through an invisible voice that the ultimate reality is the Deo Caritatis, the God of Love of the New Testament.

As to A Dollhouse – I mainly agree with your assessment, finding it, as I do, a weakly-constructed play. It is, for example, argumentatively weak in the sense that it is an implausible “stacked deck.” Torvald is an unbelievable weakling and prig; Nora is childish and stupid and her crime is the least credible thing of all, taking in the entirety of its purported circumstances. The only way in which the play can be salvaged, as I see it, is by regarding Nora as a fellow-Gnostic with Brand and Julian, making of her final exit something more ambiguous than in the usual interpretation. This requires seeing A Dollhouse in context with the rest of Ibsen’s creativity. Otherwise – and this might be the necessary position – A Dollhouse is simply a bad play. It is curious, however, that what might be the worst play of Ibsen’s mature achievement is also the best-known today, in our thoroughly feminist cultural environment. That feminists see themselves in Nora is another indictment of feminism.

Laura writes:

Thank you, Professor.

I am not as dismissive of A Doll’s House as you are. I think it has some powerful moments, such as the encounter between Krogstad and Mrs. Linde, who reforms the attorney by agreeing to love him. And the plot itself is very interesting. It’s the ending that is so abysmal, not just because of its meaning but because Nora does not remain in character. Normally so selfless and kind, she becomes cruel and cold and this strains belief.

Mr. Bertonneau writes:

My contention is that A Dollhouse (as I call it) is one of the most weakly constructed of Ibsen’s plays plot-wise, depending on implausible antecedent-acts to the unfolding of its scenario, and yet, despite its flaws and probably for entirely uncritical reasons, it remains his most-performed drama in the English-speaking countries. May I make a recommendation? Ibsen’s Lady from the Sea (1888) is one of his best plays. It’s characters are largely non-culpable and struggling to do what is right and good. The Lady from the Sea is also Ibsen’s single most most life-affirming play, ending (as no other Ibsen play does) with marriage, rather more than less happily. There was a BBC production twenty-five years ago with Ian Holm as Doctor Wangel. I should like to know your reaction to The lady.

Laura writes:

You call it “A Dollhouse” instead of the usual translation “A Doll’s House.”

Mr. Bertonneau writes:

In Norwegian, what in English always gets translated as A Doll’s House, is Et Djukkehem. The proper way to translate Et Djukkehem is, “A Dollhouse.” The point might seem trivial, but if it were A Doll’s House, then the implication would be that Nora is the “doll.” A Dollhouse moves the implication from the person to the setting, which is more in line with the salvaging interpretation of the play, partly yours and partly mine. My original degree was in Scandinavian Languages. I know Ibsen well in the Norwegian.

Laura writes:

Interesting. Yes, it does make for a slightly different meaning.

It seems to have been translated to emphasize Nora’s victimization, although Nora does speak of herself as a doll. She says in Act III before her departure, again from the Eva Le Gallienne translation:

“[Father] used to call me his doll-baby, and played with me as I played with my dolls. Then I came to live in your house —“

Mr. Bertonneau writes:

Your suggestion that the title of the play has been translated so as to emphasize Nora’s victimization is convincing. The more careful translation of the title that I urge largely de-victimizes Nora by making her an active moral agent rather than a puppet whose strings someone else pulls. Or rather, Nora becomes the victim of her own immoral deeds. That gesture in turn enables interpreters of the play to distance themselves from Nora and to judge her more objectively (and less anachronistically in terms of modern feminism) than they might otherwise do. At the same time, it requires no exoneration of Torvald, who is arguably as culpable in the total situation as Nora. You rightly remind me of the sub-plot, with its moment of moral conversion.

Laura writes:

Claire Bloom used the conventional English translation of the title when she wrote her book, Leaving a Doll’s House, about her marriage with, and divorce from, the egomaniacal Philip Roth. Judging from accounts of the book, neither Bloom nor Roth come across well in this tale of domestic hell. Ibsen’s play is a sweet love story by comparison. Bloom left her doll’s house and made money writing about it.

It’s a shame. Bloom was so magnificently talented in her youth and she permanently tarnished her image with her way of life and this book, at least for me.

Lawrence Auster writes:

I never liked Claire Bloom. She was always stiff and cold. Part of it was that widow’s peak that gave her face a sharp look.

Laura writes:

Yes, she was icy, but in certain roles this was a strength. In The Spy Who Came in from the Cold and the British thriller, The Man Between, with James Mason, her aloofness was beautiful and mysterious.

Paul writes:

I enjoyed your use of concrete facts to discuss a principle. Too many intellectuals talk about principles in abstract language only. Movies and TV, which use concrete facts to discuss principles, are usually made by liberals. This is a major reason why conservatives are at a disadvantage compared to liberals.

Laura writes:

Thank you.

Lisa writes:

A Doll’s House highlights one of the greatest temptations women face today: turning a stupid situation into a tragic one. Dolls are for play, and Nora only plays at homemaking with her drama queen exit from the family. “Every wise woman buildeth her house: but the foolish plucketh it down with her hands.” Proverbs 14:1

Laura writes:

…. turning a stupid situation into a tragic one.

Or, how about: turning marital disappointment into full-blown family collapse that will affect the lives of many others for decades to come?