The Bostonians – A Book Club Selection

January 12, 2010

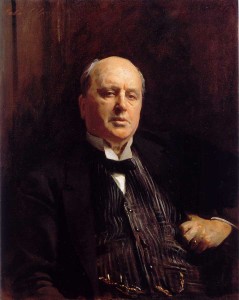

The Bostonians, by Henry James

A Thinking Housewife Book Club Selection

Before there were pick up artists, dark lords of singles bars and beta men studying the fine points of female psychology, there was Basil Ransom, a man who knew how to conquer and reform a feminist.

That’s depressing when you think about it. One hundred and twenty five years ago next month, the first installment of one of the most perceptive books ever written about the cultural decline and fall of Western women, the Henry James novel The Bostonians, was serialized in a magazine. Thirty-five years before female suffrage and long before the birth control pill was in stock, James saw it all. He foresaw the catastrophic shriveling up of the feminine life force into a strained caricature of masculinity. He knew Betty Friedan and Gloria Steinem before they ever drew a breath. He could have written the manifesto for NOW (with more eloquence) and delivered Nancy Pelosi’s first speech as Speaker of the House. He warned the world. And no one listened.

That would be too depressing if it was not possible to lose oneself in the pages of this magnificent novel, one of the greatest ever produced by an American. Forget all the sad news. Forget that you yourself have wept to the tinsel tunes of feminism. This is a great love story, a fairy tale like all great love stories and a rebuke to the swelling tide of liberalism sweeping America in the nineteenth century and finally flooding our own times.

Is the hero of this novel a beta man or an alpha? He is neither. He is Basil Ransom, defeated Southerner, chivalrous lawyer, defiant traditionalist, astute judge of character and “a man who liked to understand.” Oh, and he is good-looking in his own way:

He was tall and lean and dressed throughout in black; his shirt collar was low and wide, and the triangle of linen, a little crumpled, exhibited by the opening of his waistcoat, was adorned by a pin containing a small red stone. In spite of this decoration the young man looked poor- as poor as a young man could look who had such a fine head and such magnificent eyes. Those of Basil Ransom were dark, deep, and glowing; his head had a character of elevation which fairly added to his stature; it was a head to be seen above the level of a crowd, on some judicial bench or political platform, or even on a bronze medal.

Basil is from Mississippi and at the opening of the book, he is paying a call on his cousin Olive Chancellor in her refined Boston home on Beacon Hill. He has come to the Northeast to make a living, which will help support his mother and sister back home. His relatives live humbly, as fallen Southern aristocrats. He is unlikely to receive much asssistance or friendship from his wealthy cousin. In the words of her sister, Olive is a “female Jacobin,” a luminary in the world of Boston radicals, a woman “who would reform the solar system if she could get a hold of it” and who despite her gentrified position likes to spend time with “mediums, communists, [and] vegetarians.” She and Basil have nothing in common. It is like Kate Millet and Strom Thurmond discovering they are cousins.

Miss Chancellor is a classic gnostic, a “woman without laughter,” a believer in the religion of humanity. She is not content with the world as it is: “It was the usual things of life that filled her with silent rage; which was natural enough, inasmuch as, to her vision, almost everything that was usual was iniquitous.” James probes the psychology of the gnostic with searching intensity and shows it to be a twisted version of, even a direct response to, Christianity: “The most secret, the most sacred hope of her nature was that she might someday have such a chance, that she might be a martyr and die for something.” Where the Christian sees salvation in the next world, the gnostic sees salvation in this. As Eric Voegelin said, “Gnostic man no longer wishes to perceive in admiration the intrinsic order of the universe. For him the world has become a prison from which he wants to escape.” Olive is an “activist mystic,” certain that if women separate themselves from men and live in independence the world will be redeemed.

♦

Temperament in part drives Olive to this stance. She is morbid, nervous and shy. Like many of the most influential real-life feminists, such as Simone de Beauvoir and Virginia Woolf, she is innately non-maternal and unwifely. As James put it:

“There are women who are unmarried by accident, and others who are unmarried by option; but Olive Chancellor was unmarried by every implication of her being. She was a spinster as Shelley was a lyric poet, or as the month of August is sultry.”

There will always be women like this. It is wrong to think they can, or should be, changed. They are flukes of nature, harmless unless they try to project their own anti-maternalism on the mass of women.

Into the life of these two characters steps a third, Verena Tarrant, a young woman of sublime loveliness, preternatural charm, exquisite innocence and a distinctly lower social class than both Olive and Basil. She is the daughter of a swindler and quack healer. Verena is both highly intelligent and girlishly feminine. She has a special gift of communication, able to stand before an audience and deliver speeches of moving, naif grandeur. Olive immediately sees in this young woman an alter ego, a woman who can give to the movement of female liberation the uninhibited inspiration she herself lacks.

While Olive Chancellor represents the true believer, Verena Tarrant is the symbol of those who have fallen into liberalism’s lap not because they have believed in it but because they were dazzled by its novelty and its romantic simplicity. Olive finds it easy to convince Verena that women have been oppressed throughout history. The lovely girl, who is worshipped by every man she meets, quickly agrees.

Women have always lived on romance. Feminism didn’t change that. It supplanted the romance of man and home for the romance of worldly conquest and adventure. Verena is a romantic girl. When she meets Olive, she becomes a feminist radical out of a desire to please. She wants to please the older woman, who overwhelms her with her sophistication and intellectual breeding. She also feels pity for Olive and senses her pain. Verena reminds me a bit of a younger Sarah Palin. One gets the sense with Palin that she came to feminism by accident and by way of the same desire to please. She also possesses some of Verena’s natural charm and loveliness. Of Verena, Basil says, after hearing her speak on women’s liberation:

…. she didn’t mean it, she didn’t know what she meant, she had been stuffed with this trash by her father, and she was neither more nor less willing to say it than to say anything else; for the necessity of her ature was not to make converts to a ridiculous cause, but to emit those charming notes of her voice, to stand in those free young attitudes, to shake her braided locks like a naiad rising from the waves, to please everyone who came near her, and to be happy that she pleased.

Here is Sarah Palin on stage, younger and even prettier.

♦

“Oh, the position of women!” Basil Ransom exclaimed [to Olive]. “The position of women, is to make fools of men. I would change my position for yours any day,” he went on. “That’s what I said to myself as I sat there in your elegant home.”

Basil is not cruel, but he is not afraid of Olive. He too has a “private vision of reform.” But “the first principle of it was to reform the reformers.” He does not consciously set out to change Verena, who becomes a star on the lecture circuit with her advocacy of women’s equality, in order to prove a point. It just happens, part of the inevitable interaction between them.

It was men who granted women the suffrage and it was men who agreed to hand over their jobs to women. Men lay aside their sense of paternal honor and allowed their young daughters to sleep around and to pursue careers. Basil Ransom, on the other hand, believed women were meant for exclusive love and for privacy:

“If they would only be private and passive, and have no feeling but for that, and leave publicity to the sex of the tougher hide.”

Verena is at first appalled by his views. But women are always attracted to heros. And though he is poor and has met no wider success in life, Basil Ransom is heroic. He is heroic in his self-confidence, his certainty and his defiance of the spirit of radical democracy. “The use of a truly amiable woman,” he says, “is to make some honest man happy.” Basil offers himself in lifelong servitude on one condition: Verena must give up trying to please her public.

As I said, this is a fairy tale. In our world Basil Ransoms are rare. Most men don’t believe in themselves as men. Those who do are often too crude and worthless to be worth the time. This is a somewhat painful book to read, I won’t deny it. It is filled with entertaining episodes; great descriptions of New York, Boston and Cape Cod; a keen grasp of the ersatz reigious movements of the late nineteenth century; absorbing dialogue and memorable characters who will seem familiar to anyone mildly observant today. But it is cause for sober reflection. Basil Ransom was born 125 years ago. He has long since come to seem as mythical as Odysseus and as ancient as Agamemnon.

Ransom was an outsider and a critic of his age. He thought it “talkative, querulous, hysterical, maudlin, full of false ideas, of unhealthy germs, of extravagant, dissipated habits, for which a great reckoning was in store.” Imagine what he would have said of ours. No wonder Verena fell for him.

![bigstockphoto_Black_Flowers_4800530[1] bigstockphoto_Black_Flowers_4800530[1]](https://www.thinkinghousewife.com/wp/wp-content/uploads/2010/01/bigstockphoto_Black_Flowers_480053011-150x105.jpg)

—- Comments ——

Alex A. writes from England:

I enjoyed reading your sympathetic consideration of The Bostonians: it’s very shrewd and well written. The end of your penultimate paragraph has a couple of sentences that say a lot in an admirably compressed and elegant form:

“Basil Ransom was born 125 years ago. He has long since come to seem as mythical as Odysseus and as ancient as Agamemnon”.

For all I know, not many readers would interpret James’ novel as a text for the times. But studied in the light of the follies of late twentieth century feminism, it surely resonates across the last century and a quarter. You’ve done the book a service by drawing our attention to its subtle commentary on “the position of women” – both then and now.

The works of Henry James have a intimidating reputation. (I found it difficult to finish The Ambassadors). In my view, The Bostonians and The Europeans are probably his two most “accessible” novels. They are easy to read and perhaps unexpectedly comical. No belly laughs of course, but witty and droll.

Laura writes:

Thank you.

Yes, this is one of James’ easier works to read, longer but no more demanding than The Turn of the Screw, Portrait of a Lady, and Washington Square. There are many funny moments, especially those including Miss Birdseye, the ascetic Boston radical and a variation on Dickens’ Mrs. Jellyby, and Doctor Tarrant, the mesmeric healer who is Verena’s father.

By the way, the 1984 movie version of the book starring Vanessa Redgrave as Olive Chancellor and Christopher Reeve as Basil Ransom is well done.

Karen writes:

Laura writes: It was men who granted women the suffrage and it was men who agreed to hand over their jobs to women. Men lay aside their sense of paternal honor and allowed their young daughters to sleep around and to pursue careers. Basil Ransom, on the other hand, believed women were meant for exclusive love and for privacy:

“If they would only be private and passive, and have no feeling but for that, and leave publicity to the sex of the tougher hide.”

Throughout the world women have gained the vote and worked in professional jobs in the twentieth century, even in Islamic Pakistan and Bangladesh, Iraq and Afghanistan. The Western world now lags behind the Asian countries in the education of women (and men) both in the West and in Asia. Only in the Western world has marriage and the family collapsed. And only the West has a welfare state. Hence it cannot be concluded that female voters or educated women are the cause of the West’s problems. However it does seem to fit with the trend of harking back to the 19th Century as a golden era to which we should aim to return. There is no going back. Times have changed. The Chief Economist of HSBC stated last week that global economic power and wealth have shifted irreversibly to Asia. People in the West have not woken up to this fact. But the reality of that will soon hit home in declining living standards. The West’s power and wealth was squandered by its failure to adhere to its traditions and maintain them and its relapse into hedonism.

India produces the highest number of female graduates and voters in the world but there is no demand for a welfare state, divorce or abortion. Sri Lanka had the world’s first female president but she did not start welfare or encourage divorce or sexual promiscuity. Indira Gandhi lead the world’s largest democracy but did not change the tradition of the country. India has the highest number of educated women in the world but the lowest divorce rates.

It is a fact that the Asian countries adapted better to the changes of the 20th century better than the West did and at the start of the 21st century have replaced the West as the dominant economic powers. The strength of these countries is in their long family traditions of arranged marriage and extended family which provides a better framework for society and support system for the individuals within that society. It also provides an excellent system for the preservation of wealth and social stability. The West’s focus on the individual and the pursuit of individual liberties and fantasies has been a failed experiment. Women’s pursuit of careers doesn’t wreck families but sexual promiscuity does. Men laid aside their sense of paternal honour when they stopped arranging suitable marriages for them as they did in the past and they still do in the rest of the world.

Laura writes:

I entirely disagree with Karen, but we clashed on this before and I recommend the discussion following my article Why We Must Discriminate. Let me make a few quick points in response.

The effects of careerism in women are only beginning to be felt in Asia and it has indeed led to increases in divorce and declines in birth rate. Nevertheless, Asia is not the West and the West is not Asia. There is a higher degree of individualism in the West which will always entail a greater emphasis on personal love. Arranged marriage cannot be sustained with any kind of respect for the individual in a world where older women, the main gatekeepers of arranged marriages, are preoccupied. The idea is an absurdity in contemporary America where most women don’t have the energy or inclination to monitor who their daughters are sleeping with let alone hunt down husbands for them. In the West, sexual restraint has always entailed adult supervision. That takes time. I’m all in favor of more parental guidance in marriage, but it isn’t going to happen in an egalitarian society that assigns women the roles of men.

Contrary to the West not being able to survive economically without careerism in women, it cannot survive economically in the long run with it. [Note that I am talking about widespread careerism, not about women in the workforce or careerism in a few.] The birth rate among whites in America and Europe is below replacement level. The moral and educated workforce needed to sustain any advanced democracy cannot be produced by distracted women. There simply are not the family networks, stable communities, and decent schools to provide the atmosphere or practicalities adequate to child-rearing. Family is the foundation of political liberty and families are not created in two free hours a day. Furthermore, the dynamism and energy of the West, so vital to its economies, are outgrowths of both male and female initiative and resourcefulness within their separate spheres. The widespread emasculation we see is dangerous and demoralizing and is an inevitable counterpart of female aggression. Careers for women don’t just happen; they are the product of concerted effort and individual aggression.

Let’s just say, however, that divorce could be seriously restricted in the West and arranged marriages similar to those in the East could somehow be brought about. In addition, let’s say young women gave up sex entirely during the ten years or so before marriage in which they’re establishing their careers. The loss of these freedoms, which are the only compensations most women receive for lives of non-stop work and which offer them illusory romance in exchange for grueling industry, would likely lead to a voluntary retreat from careerism in women. Remember, we are not talking about a world where women have nannies and cooks, but one in which they face 18-hour shifts, long commutes and inadequate time to instill basic manners and virtue in children.

Brenda writes:

I’m barely familiar with Henry James’ works, having read Washington Square. It was an enjoyable story, moved well, & had believable characters. In fact, the movie The Heiress(1948 or ’49, I think) starring Olivia de Havilland was based on Washington Square. You have whet my appetite with your review of The Bostonians, & I will see if I can get it from our public library. Many thanks!

Laura writes:

You’re welcome. I hope you enjoy it.

By the way, I love Washington Square, both the book and the movie version you mention. The James novella is a small masterpiece. Again, it is a great defense of authentic femininity. It is essentially the story of a feeling woman overcome by the excessive rationality of a powerful man. James understood women and he should be required reading in any “women’s studies” course.

Lydia Sherman writes:

If you could know with what delight I read your recent post on The Bostonians! I have many thoughts about this book and about your review.

I also viewed the film version, with Christopher Reeves as the Southern gentleman. The film did not quite capture the significance of his Southernness and his view of the importance of women to men in their need to build family and society. However I suspect the film writers endeavored to allow the Southern accent and his gentlemanly behaviour to explain it all.

I have studied Southern culture and come from a Southern family, so I know there is something more to this character than the film supplied. A Southerner is more than who he is right now. He is the collection of habits and beliefs from a Christian heritage, and a land which his forefathers inhabited. Few Southerners want to leave the place of their birth, as opposed to many other Americans, who take up roots and go elsewhere, so a Southern man of the time would have been someone whose very personality embodied the land of his birth.When such a man spoke, you didn’t just hear his accent: you saw the rolling Mississippi River and the mansions on the hillsides.

He is a gentleman no matter what, and that is one reason the South lost the war. While the Federals burnt the towns and villages in order to “destroy the chivalry” as General Sherman wrote (“We will make such a wasteland of the Shenendoah Valley that if a crow flys over it he will have to bring his own rations”), Robert E. Lee refused to harm women and children. He intended to keep to the battle field and fight other soldiers to keep them off their newly formed Confederate country, but his opponent used other tactics.

A gentleman of the South, at that time, would have truly mourned the demise of women, for one of the sources of great admiration of the South was the beautiful, cultured, hospitable and refined women. During the war, it was their women who stayed home and educated the children and taught them to honor God, parents and country. A study of the culture of the South, does enhance an understanding of this novel.

The Northern states at the time were looked upon as more industrious, rather hurried and business-like. The Southerners were mostly farmers and tradesmen, and, partly due to the climate and the prosperity of the time, relaxed and hospitable.

I believe in the book, “The Bostonians,” the refinement of the gentleman is like salt and light to those ladies bent on living without men –a society which saw itself as progressive but failed to understand the sad results. He comes into the scene being his natural self: well-mannered, admiring of women, gentle, etc. Olivia, his cousin, thinks, “Doesn’t he know that it is naive to be a gentleman? Doesn’t he know that we are progressive?” Indeed, that is the way I am often treated–as though my world is dead and the next generation is “it,” and has all the answers.

Basil’s strategy, if you want to call it that, was to win with love, a lesson that most feminists ignore as trivial or manipulative. Henry James was right: With all the distractions presented to women, men would end up competing with ambition and careers, which would create enormous anguish and conflict. Feminism was created to give women careers instead of families and homes. The contrast in the book was clear: those who chose something other than a husband and a home, might have an uncertain future and would end up forever trying to push their luck.

You stated that Henry James must have seen the future when he addressed the outcome of feminism in his book. Yet at the same time, many Christians were teaching women that if they left their post at home, there would be a destruction of society: lost, undisciplined children, women whose feet would not stay, and a general feeling of unrest. Mothers warned their daughters that women belonged at home and were needed there to guard future society. I imagine there were a lot of common people discussing this issue during Henry James’ lifetime. Even those not particularly religious saw the danger ahead.

Laura writes:

Thank you for these wise insights. Lydia is correct. This is very much a book about North vs. South, liberalism versus traditionalism, self-interest versus love. James seems to suggest that the radicalism of Olivia Chancellor is a Christian heresy, a toxic mixture of Puritanism and Northern individualism.

Laura adds:

Thomas Bertonneau sends this link to an article he wrote for the journal Anthropoetics on The Bostonians, in which he reflects on the desire for martyrdom in the character Olive Chancellor. He notes the irony of Olive’s claim to be advancing the interests of all women while consciously thwarting the desires of Verena. Olive is determined that Verena should not marry Basil Ransom.

Mr. Bertonneau wrote:

But this is only to say that all utopian agendas, which insist on a guarantee of satisfaction, must issue in the compulsory participation, hence in the negation as self-determining subjects, of those who would rather not participate, because they have some other plan.

Thomas Bertonneau writes:

For a number of years my article, “Like Hypatia before the Mob,” was one of the most-cited articles in Henry James studies, almost always by people who were determined to refute it; but the “refutationists” were inconsistent, since Henry James studies consisted then, as they consist now, of trying to denounce and diminish Henry James and his work as much as possible, on the usual charges of “sexism, racism, fascism,” etc.

Laura writes:

I did not know there was an active effort to denounce his works.

Thomas writes:

Yes! It’s stunningly counter-intuitive, isn’t it? But that’s what happened to literary studies almost in toto beginning in the 1980s. According to the “Dead White Male” theory of existence, if James were famous, it could only be because the “Patriarchy” had calculatedly promoted his books over unknown books by women and people of color. Ergo, James was a “beneficiary of privilege” whose reputation had to be “deconstructed.” They’ve been doing the same to Joseph Conrad and Jane Austen. James poses a problem, since he seems to have been homosexual; but the “School of Resentment” gets around this by accusing him of having been a “closeted homosexual,” which is, of course, a great sin in their view.

Laura writes:

This is surprising with James because he is so sympathetic to women. As I said, what could be a more searing portrait of male dominance of a weak woman than Washington Square?

As a literary scholar, you must feel like you’re perpetually standing on the deck of a ship in a major gale, holding on to the railings for dear life.

Thomas replies:

Yes, yes, yes! Sympathetic to women, James was! Maggie Verver (of The Golden Bowl) is the most heroic woman in American letters, demurely putting two afflicted marriages back together with a subtlety so fine that it rises into the realm of the moral sublime!

Lydia Sherman writes:

What was your opinion of the female physician in The Bostonians? I felt that she was quite pleasant and not at all bitter towards men. Somehow, she had achieved her career without the help of the radical femininists, and seemed to acknowledge that she was there partly because of help she received from men. What do you think?

Laura writes:

Mary Prance is a boarder in the home of the radical elderly activist Miss Birdseye. She is a “doctress,” or physician. Here is Basil Ransom’s first impression of her:

The little medical lady struck him as a perfect example of the ‘Yankee female’ – the figure which, in the unregenerate imagination of the children of the cotton-States, was produced by the New England school-system, the Purtian code, the ungenial climate, the absence of chivalry. Spare, dry, hard, without a curve, an inflection or a grace, she seemed to ask no odds in the battle of life and to be prepared to give none.

Doctor Prance is a fascinating character. She is one of those genuinely masculine women who do not glamorize androgyny because nature has foisted it upon them. She is set apart from the storms of male-female relations because she is not constitutionally suited to love or marriage. She represents a true-to-life type, a woman who is more a man. She recognizes herself as an outsider. There is no bitterness, yet she is set apart in the way someone who is chronically ill is set apart from the healthy. She seems heroic. She and Basil have a brief conversation about female activism shortly after their meeting.

“Men and women are all the same to me,” Doctor Prance remarked. “I don’t see any difference. There is room for improvement in both sexes. Neither of them is up to the standard.”

Lydia writes:

I didn’t observe the bitterness in Dr. Prance that the feminists had. She was confident and knew she was different, but she was a doctor because she wanted to be. She worked for it and was not given the privilege just because she was a woman. She seemed to admire men more, because she experienced the accomplishment. She seemed kinder than the feminists. She is so different from Olive, who insisted on changing the unchangeables–the roles of women, the things their sex are better at, the universe, etc.

James’s analysis of Olive fits today’s philosophies as well as they are intent on breaking down Biblical values by a strategy of arguing or discussion, assuring that no conclusion will be reached (unless it is theirs). We see this going on with the emergent movement in churches, where such tactics are designed to dismiss any authority, whether it be in the Bible or in church leaders. The character of Olive is so telling of many women today, who insist that things that are so, should not be so, and things that are not so, should be. Attempting to change it their way is like trying to get water to flow from a rock, without the power of God, and as they never make any progress, their frustration increases. They build up a resentment toward those who are quietly submissive to the gifts that come their way in the form of love and marriage, children and homes to look after. Like Olive, the radical feminist cannot see the young woman who chooses marriage, and the work of raising a family, as important progress.

Laura writes:

The irony of Dr. Prance, as I said, is that she is an innately masculine woman. If anyone would be outraged by women not having the opportunities of men, you would think it would be a woman who genuinely needed to function as a man. But she was focused on her work. It was everything and she did not wrestle with any conflict to be anything but a doctor nor did she feel a need to make other women more masculine to vindicate her own choices.

Alex A. writes from England:

This absorbing discussion of The Bostonians is a good example of what sets The Thinking Housewife apart from so many other blogs of quality. (The range here is wide and fertile, and the scenery more varied, so to speak.)

Henry James is emerging as a trenchant critic of the feminism yet to come – which I had only vaguely realized before. It would be very interesting to read what you have to say about the character of Isabel Archer – conceived as “a certain young woman who affronted her destiny” – when/if you decide to write about The Portrait of a Lady.

Laura writes:

Thank you.

Henry James offers many possibilties for future book club selections. By the way, I hope to post later today in a separate entry a list of the books I will be discussing in the weeks ahead so that anyone who wishes can participate in discussions.

Karen I. writes:

I ordered my copy of The Bostonians today so I can participate in your Book Club. Others who want to participate may like to know it can be purchased used in very good condition at Amazon.com for as low as 77 cents. I spent under $5 to have it shipped to me buying it used at Amazon from a seller in a nearby state. The nearest book store is about 20 miles away and books are expensive there so this great for me.

Laura writes:

Alibris is also good for used books.