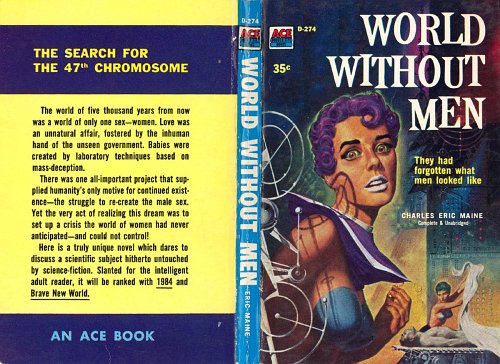

World Without Men

August 18, 2010

Charles Eric Maine’s Novel of Lesbian Dystopia

By Thomas F. Bertonneau

[Note: Another article by Bertonneau on World Without Men appeared this week in The Brussels Journal. The essay below was written for readers of The Thinking Housewife.]

BY WAY OF INTRODUCING both my topic and myself I might say that I am a lifelong aficionado of science fiction who is familiar with the genre in depth. When I teach my course on science fiction at SUNY Oswego, I concentrate of classics texts of high literary merit – those by Edgar Allan Poe, H. G. Wells, Olaf Stapledon, and Ray Bradbury. When I pursue my hobby I am less selective. When I discover an unknown paperback title in a second hand bookshop, I frankly judge the item by its cover and where content is concerned I hope for the best. Most of the mouldering paperbacks fall short of memorability. Occasionally, however, I stumble across a jewel among the rubble, a short story or novel more or less forgotten that, for one reason or another, merits contemporary re-visitation. One such, which I encountered again recently after a lapse of decades, is Charles Eric Maine’s World Without Men (1958)**, a novel about the long-term implications of birth control, abortion, and the so-called sexual revolution that treats these matters in a bold and prescient way.

It is safe to say that World Without Men could not be published today. Editors, evaluating it in manuscript, would deem it absolutely politically incorrect; they would act to prevent Maine from perpetrating the lese majesté inherent in a story that unstintingly defends the idea of a natural order of human existence and which, describing homosexuality without embarrassment as “perversion,” argues that feminism (inherently homosexual in Maine’s view) is a totalitarian ideology. Better to suppress such a thing.

In World Without Men,Maine tells a story in five quasi-independent but serially related episodes, unfolding a chronology that begins late in his own Twentieth Century and culminates fivethousand years from now in the year 7000 AD. The first and fifth stories take place in 7000 AD; the setting and a recurrent point-of-view character unify them. The second, third, and fourth stories fill in the chronological gaps, the second taking place (as one might suppose) before the advent of the Second Millennium, the third taking place fifty or seventy-five years after the second, and the fourth taking place perhaps two millenniabefore the first and the fifth (around 3000 AD). The five episodes are (1) “The Man,” (2) “The Monkey,” (3) “The Girl,” (4) “The Patriarch,” and (5) “The Child.” It seems logical to discuss “The Monkey” first, since this story represents the cause in response to which the other stories represent the consequences. World Without Men is a novel about the liquidation of the male sex.

“The Monkey,” whose title has various social-Darwinian connotations, concerns the invention of a birth-control drug called Sterilin. Maine’s perspective-character is Phil Gorste, a research chemist employed by Biochemix Incorporated; this is a large industrial-pharmaceutical concern presided over proprietarily by one E. J. Wasserman, the fifty-something widow of the company’s founder, who is many years deceased. By the time they reach the end of “The Monkey,” readers have reason to suspect all spousal deaths although Maine never explicitly says that Wasserman killed her husband. Gorste discovers, however, that his wife, Anne, killed her previous husband, Gorste’s co-worker Drewin. Gorste and Anne had together betrayed Drewin, who sought revenge on Gorste by exposing him in the laboratory to a concealed source of raw radiation. Drewinsupposedly committed suicide; Gorste believes, erroneously as it turns out, that gamma-ray exposure has rendered him sterile, and he worries how Anne, who wants a child, will react to the news. Maine offers this tangle of wretched lives and spiritless existences as the context of his central storyline, the production of the drug.

The frigidly pragmatic atmosphere of the business setting thus reflects the degeneracy of the people who supply the human resources of the enterprise. The scientists are utterly compartmentalized, specialists in the narrowest sense. Wassermanand her executive board members are bullying money-grubbers, who demand a marketable product.

The heart of “The Monkey” consists in the discussions about how to present Sterilin to its intended market of young fertile women. One executive person says, “birth control is only half of the sales story”; he adds that, “Sterilin has a more positive selling angle,” namely “uninhibited enjoyment of the pleasures of life.” Wasserman wants Gorste to perfect the drug in the form of “tablets… pleasant to the taste… invigorating… with fizz, perhaps.” For a slogan, a marketer suggests, “Sterilin – For Modern Feminine Hygiene.” The pills will be packaged in a pink, heart-shaped compact. In private conversation, when Gorste timidly expresses misgivings of “conscience” to Wasserman, she dismisses his qualms: “Conscience… is a simple matter of conditioning.” With sophistic relativism, Wasserman claims that, “moral conscience is largely a matter of geography.” Coming to her point she affirms that, “Sterilin… is going to accelerate the process of moral emancipation”; it will, she says, lead to “profound changes in morality… changes for the better.”

Wasserman seduces Gorste, knowing that guilt will silence him. Later that evening Anne startles Gorste by announcing her pregnancy. Believing that, because he is sterile, she must have betrayed him (just as she had betrayed Drewin), he kills her. As Anne lies dead, Gorsteanswers the telephone to receive the news from his doctor that he is not, in fact, sterile. He telephones for the police, arranging to be arrested. So ends the story.

“The Girl” narrates the social and political consequences of what Wasserman cynically calls “the process of moral emancipation.” The mass of women in developed societies respond to the allure of their supposed liberation by embracing Sterilin almost universally. Birth rates fall, but even more alarmingly the proportion of male births declines asymptotically. Governments respond by covert totalitarian measures. Thus, “all the radio and television services are controlled by the government,” the better to conceal the crisis, as Brad Somer tells his interlocutor. Somer, a journalist, thinks that Rona, his contact, is a government official willing to help him in publicizing the real story. Female dedication to Sterilin forces the nations to adopt a uniform scheme: “Laws must be created and enforced to compel every woman of mature age to spend a period in what might be termed a fertility center, where she would be impregnated and made to bear a child; the number of children each woman would be required to bear during her lifetime would depend on the existing birth rate statistic.” At first, women were permitted to choose from a pool of genetically selected men, but as the number of men began to dwindle, the practice shifted to “artificial insemination.”

While such measures secured a replacement birth rate, they did nothing to stimulate male births, which had reached zero. “It was sterility in reverse, a vicious and uncontrolled reaction aroused by the indiscriminate use of Sterilinon a world-wide scale.” The best that science could by then devise was a method for inducing artificial pregnancy. “Women had chosen sterility in the interests of sexual freedom; nature had responded with a fine sense of irony by eliminating the male sex.” “The Girl” ends with Rona revealing herself as a covert agent who arranges for Somer’s arrest and execution. The truth must not be told.

“The Man,” the novel’s first episode, specifies the ultimate consequence of the catastrophe, as it manifests itself some five thousand years in the future: The consolidation of a global, totalitarian lesbiocracy. Maine settles his point of view on a character named Aubretia Two Seventeen, a middle level functionary in the Department of Press Policy and Information; Aubretia is essentially a censor and propagandist, vetting information in order to protect the state from any revelation of its true nature. Aubretia is a typical denizen of the “Lon” (London) of her day, or of anywhere else in her world. Aubretia is an oddly de-sexed female, girlish in appearance; she dresses her “atrophied breasts” with “silver lacquer” and paints her lips “snow white.” Yet while de-sexed, she is also weirdly eroticized, thinking of Aquilegia, her albino lover, while she accouters herself in a provocative, semi-nude outfit.

When Aubretia arrives at her place of work and begins scanning the daily news, Maine takes the opportunity to give the reader glimpses into the cultural jejuneness of the all-female utopia. The infrastructure in formation in “The Girl” has become fixed; all entertainments are erotic; everything operates according to strict, statistically determined routines.

Summoned to confer with a higher official, Aubretia learns of the discovery, at the North Pole, of a male cadaver preserved by the cold in a crashed spaceship that became embedded in the ice. When a scientist shows her the corpse, she feels queasy and alienated. These are signs of a rupture in her conditioning, her internalization of the “parthenogenetic adaptation syndrome.” All members of the lesbian society are conditioned, as they must be. So unnatural and fragile is the “syndrome” that the mere sight of a male can undo it. The vision of the Arctic male deeply disturbs Aubretia. Her lover notices the disequilibrium, solicits the story, and, seeing an opportunity, reveals that she is actually a member of the dissident underground. She discloses to her shocked partner that the supposedly utopian order is based on lies. Men did not, as the state claims, disappear naturally, but died out as the result of tampering with procreation (Sterilin); women do not presently conceive by natural parthenogenesis, as propaganda insists, but by induced parthenogenesis.

Most importantly, the lesbian orientation is not natural; but rather, it is part of the conditioning that all children undergo while being raised from infancy to young adulthood apart from their birth mothers in the state crèches. (Maternity is necessary, but the social arrangement prevents it from interfering with the hedonistic lifestyle.)

Aubretia, outraged, attempts to broadcast the story of the Arctic cadaver. Police monitors suppress the broadcast, arrest Aubretia, and send her away to be psychologically re-conditioned. In the second part of the story, Aubretia has been re-settled in “Birm” (Birmingham), with great gaps in her memory. Aubretia’s new lover, readers guess, is a police minder, in one of whose rare absences another member of the dissident underground pays Aubretia a visit, looking for help in flight from police apprehension. Her name, revealed in “The Child,” is Deurina.

Deurina tells Aubretia: “It’s all a lie… We are creatures of sex living by force and unnaturally in a sexless society… The government tries to tell us it’s normal, but in fact it’s abnormal. We’ve become a race of lesbians.” Deurina divulges that the state rests on a dual basis of enforced parthenogenesis and “mandatory euthanasia,” the latter applied to anyone whose level of productivity falls below a statistically determined minimum or whom the authorities deem a dissident.” Deurina frankly calls the status quoa “perversion”; it is based, she says, on “statistical birth and murder and on a homosexual morality… corrupt throughout.” Aubretia cannot overcome her conditioning. While Deurina sleeps, Aubretia summons the police.

“The Patriarch” tells the grim and wretched story of the last man alive, a degenerate prisoner kept for scientific purposes in an Antarctic laboratory; he escapes confinement only to die in the frigid night of a polar winter.

“The Child” revisits the milieu of “The Man” and reintroduces Aubretia in its concluding section. In “The Child,” centuries of cytoplasmic experimentation have produced, at last, an artificial male gamete, and by means thereof, a unique male child. A supervisor warns personnel that the infant in the incubator amounts to no more than “the result of a successful experiment in micro-cytology” in respect of which “there is no question of human status.” Indeed, the lesbian state so fears the implications of a male child in its plain existence that it has invoked a death sentence. Koralin, a laboratory assistant who feigns willingness, accepts the detail only boldly to convey the child off the premises. Already a dissident, Koralin experiences a surge of maternal feelings on coming in contact with the infant. Such feelings are precisely what officialdom wants to prevent because they threaten the “parthenogenetic adaptation syndrome.” Fleeing, Koralin comes to Aubretiaon the slim chance that she can revive the latter’s distaste for actualities.

Koralin tells the frightened Aubretia, “This baby… could be the savior of womankind.” Maine selects the term “savior” carefully, pointing back by means of it to Gospel references in “The Man.” (Deurina corrects Aubretia when Aubretia recalls vaguely and erroneously that Christ was a woman.) Koralin likens the lesbiocracy to something inhuman and moribund – “laboratories, experiments in human embryology, fertility centers, induced parthenogenesis, cultivated lesbianism” – that sacrificially seeks the destruction of a mere baby. “There was another parthenogenetic male,” she tells Aubretia, “a miracle child that was referred to as the savior of mankind,” whom “the state set out systematically to destroy.” Sharpening the parallelism, Koralin says: “For thousands of years the world has awaited a second Messiah. And now he has arrived… authority will attempt to destroy him before he destroys it.” Maine has carefully not attributed divine status to the child; he has only characterized the child as supremely sacred, to be guarded from predation at any cost.

I would underline that Maine’s narrative, which first saw print fifty-two years ago, links symptoms of cultural decadence like mainstreamed pornography and socially licensed promiscuity to the ideology of feminism. Maine’s narrative seeks to illustrate the logical outcome of the feminist claim of male toxicity. World Without Men implicates one contemporary headline after another: Gay marriage, artificially inseminated single mothers, and death-panels in connection with so-called healthcare. Advertisers nowadays market contraception on television in exactly the gauzy manner that World Without Men predicted. Maine was an unabashed apologist for what normal people used unhesitatingly to advocate as, yes, normal, but which left-liberal elites nowadays routinely revile as a legacy of prejudice, intolerance, and bigotry to be absolutely and finally eradicated.

** World Without Men was reprinted in the 1960s in a slightly altered version under the title Alph.

— Comments —

Y. writes:

World Without Men implicates one contemporary headline after another: Gay marriage, artificially inseminated single mothers, and death-panels in connection with so-called healthcare.”

Though not directly implicated in the novel, don’t forget that oral contraceptive’s estrogen in the water is thought to be reducing male fertility:

Declining Male Fertility Linked To Water Pollution

New research strengthens the link between water pollution and rising male fertility problems. The study, by Brunel University, the Universities of Exeter and Reading and the Centre for Ecology & Hydrology, shows for the first time how a group of testosterone-blocking chemicals is finding its way into UK rivers, affecting wildlife and potentially humans…

Earlier research by Brunel University and the University of Exeter has shown how female sex hormones (estrogens), and chemicals that mimic estrogens, are leading to ‘feminisation’ of male fish. Found in some industrial chemicals and the contraceptive pill, they enter rivers via sewage treatment works. This causes reproductive problems by reducing fish breeding capability and in some cases can lead to male fish changing sex.

Rita writes:

I love the World without Men book review. Wish someone had listened to the prophets back in the 60s.

Mr. Bertonneau writes:

Thanks to “Y” for the important reference. We know at least two consequences of “the pill.” One is the dissolution of traditional sexual morality, with the paradoxical result that women collaborate in the male fantasy of universal availability without contract and that men immediately become less masculine because their refusal to submit to the contract (marriage) makes them inveterately childish. But there are undoubtedly many more consequences, including the biochemical consequence of reduced male fertility, as massive amounts of estrogen enter the hydraulic cycle and the food chain. Of course, reduced fertility and reduced masculinity might be one and the same phenomenon, as the Viagra craze suggests. And what about the consequences of Viagra in the ecology? World Without Men is what Orwell, who had a good sensibility for popular culture, called a “good bad book.” It is commercial fiction, but written by an intelligent writer who understood what far too many people seem not to understand – that everything has consequences.

Mr. Bertonneau adds:

I offer thanks to Rita for her positive comment. For a number of years I have been doing what I like to call “cultural archeology.” The phrase means looking into the forgotten discourse of the not-so-distant past to see whether our contemporary situation was foreseeable. Sometimes the source is not unknown – José Ortega y Gasset’s Revolt of the Masses is a good example, as is Oswald Spengler’s Decline of the West. Sometimes, as in the case of Maine’s World Without Men, it is contemporarily entirely unknown. I have argued recently – in a discussion of college-student literacy (or the lack thereof) that contemporary culture is, by deliberate design, “historyless” and “memoryless.” In a society dominated not by real, but by commercial and political culture, the past is the first victim. Since the past and conscience require one another, a “historyless” and “memoryless” culture is a grave danger to itself. A novel like World Without Men, while it is not a literary masterpiece, reminds us (startlingly, I would say) that in the relatively recent past, even popular entertainments could be gravely serious, and even an “entertainment writer” could foresee disturbing trends.

George writes:

Mr. Bertonneau said: I have argued recently – in a discussion of college-student literacy (or the lack thereof) that contemporary culture is, by deliberate design, “historyless” and “memoryless.”

Could Mr. Bertonneau expand on what exactly what he means by “deliberate design“?

Mr. Bertonneau writes:

By “deliberate design” I mean two things mainly. First, with respect to so-called popular culture, North American society has long since embraced the MTV formula of entertainment-consumerism, in which, on a weekly basis, new crass junk replaces old crass junk, to induce the tasteless masses, beginning with the young, to buy the commodities put on sale by the showbiz industry in all its manifestations. Second, with respect to education, a similar immediate-replacement model has long since taken hold, which is based on the denigration of the past and which aims initially to vilify that past and then to erase it. As to the first of these points, a perusal of The Thinking Housewife will affirm the almost exclusive currency of the vulgar and the jejune in reigning commercial culture. (The prostituted Mily Cyrus and “Lady Gaga,” to give but two examples.) As to the second, look to any high school American history textbook or to the most-taught history book in American higher education, the despicable Howard Zinn’s execrable People’s History, the purpose of which is to make middle-class students ashamed of their national and cultural heritage on the basis (how else to put it?) of Stalinist lies.

Now we come to the really insidious aspect of this dual phenomenon. The strictures of political correctness – those of the Howard Zinn-type hatred of everything traditional – thoroughly infuse the products aggressively marketed and sold by Hollywood and the music industry. (A big component of political correctness, incidentally, is dogmatic feminist hostility to men.)

The purpose of contemporary commercial culture (or entertainment culture – one wants to put quotation marks around all these terms) is to inculcate anti-traditional bigotry by riding it, piggyback, on what amounts to pornography. In obliterating the past and in coarsening taste, the mongers of junk-entertainment create the ideal subject for crude propaganda.

It might seem that these remarks stray from World Without Men, but that would not be so. While Maine’s representation of censorship of news, obliteration of history, and distracting eroticized entertainments for the masses is not original to him (the prototypes may be found in Huxley and Orwell), his linkage of them to birth-control and feminism is a real insight.

My recent article, “Forget U.” , for the John William Pope Center addresses some of these themes.

Y. writes: