Quality vs. Equality: A Talk on Robert Pirsig’s Zen and the Art of Motorcycle Maintenance

March 29, 2011

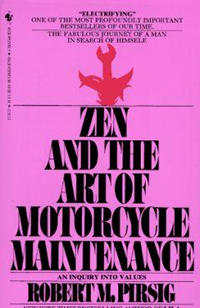

The essayist Caryl Johnston recently gave a lecture in Chestnut Hill, Pennsylvania on the works of Robert Pirsig, author of the bestselling book Zen and the Art of Motorcycle Maintenance. Pirsig’s philosophical novel, which is not really about Zen Buddhism or motorcycles, was an enormous hit in the 70s, selling five million copies after initially being rejected by more than 100 publishers. Johnston argues that Pirsig’s “Metaphysics of Quality” offers a satisfying remedy to the moral and intellectual decline caused by modern rationalism. Johnston is author of several books, including Consecrated Venom: The Serpent and the Tree of Knowledge and From Boston to Birmingham. Her entire talk is posted below.

IN SEARCH OF QUALITY

Good afternoon ladies and gentlemen. Thank you for coming to this talk about the works of Robert Pirsig: Zen and the Art of Motorcycle Maintenance: An Inquiry into Values (1974) and Lila, An Inquiry into Morals (1991).

I believe these books have something important to say to us today. Zen and the Art of Motorcycle Maintenance was immensely popular and sold millions of copies in 23 languages. Yet its message did not penetrate intellectual or elite opinion to any measurable degree.

I think this is unfortunate. Pirsig’s philosophy provides real insight into some of our persistent problems. We forget how the capacity to act effectively depends upon the ability to think. Without clarity of thought no action is possible. And in the long run, “no action” in the end means a loss of the good. Pirsig’s search for values reminds us of the purpose of thinking — which is to help us lead a better life.

In my view, our deteriorating national situation is ultimately owing to the decline of thinking, or rather to confusion about how we think about values. To pull ourselves together as a nation and affirm a common future will depend upon our decision to develop our thinking capacity and to demand a better quality of thinking in our public life.

One of the main tasks of thinking is the ability to make evaluations, that is, intelligent moral judgments, which involves defining acts as good or bad, better or worse.

Moral relativism has deeply entered into our social habits. “It’s just your opinion” and “It’s all relative” are often heard in moral debates. Even the idea of making a judgment, of rating things in a scale of better or worse (except in consumer surveys!) has become repugnant.

But I doubt anyone here has ever acted on anything important – say, voting, deciding to get married, which school to go to, which church to belong to, – without consulting his or her inner soul and inclination about what is best, what is right, what feels or seems good. When something is really important to us, we do not hesitate to affirm moral values and standards. Why we have trouble making these evaluations with larger issues is something Pirsig’s philosophy greatly helps explain.

This consulting, this listening we do with ourselves, is what Pirsig calls Quality – or rather, what we are doing is responding to Quality. Quality is the primary event. It’s where our mind (our thoughts, feelings and preferences) interacts with matter, the things “out there,” the objects and events in the world.

This Quality event, this act of saying that something is good, is the first step in what Pirsig calls his metaphysics.

What is metaphysics?

The term itself just happens to come from the title of the book that Aristotle wrote after his work on Physics – ‘meta’ meaning ‘after.’ Meta ta physica was the book Aristotle wrote after ta physika.

I define metaphysics as the disciplined inquiry into the fruitfulness of ideas. I like to think of metaphysics as an awakener. Metaphysics prods us out of our habitual states, of taking things for granted. This prodding, this goading into awakeness, is the enemy of the automatic. Robots have no metaphysics.

This would indeed be a topic for a whole new lecture. But let us move on.

Now, there are different ways of viewing the world. Pirsig calls the dividing of the world into “subjects and objects” or “mind and matter” the metaphysics of substance.

The problem with the metaphysics of substance is that values (what I think are important, better, deeper, more spiritual, etc.) can only exist in the “subject” or “subjective” side of the equation. A subject can have all the values he wants! But what difference will it make? Where are values? They are nowhere in the world. Objects are value-free, the world is indifferent to values, science claims to be objective, that is, indifferent to values. This attitude is everywhere. It has permeated science and all disciplines that aspire to emulate science.

This is called the ‘fact-value’ dichotomy, and it has been basically unchallenged in Western philosophy for several hundred years. The question quality – values – morals – basically has been banished. They are not part of the object, so they just become part of the subject, subjective.

By contrast, in the Metaphysics of Quality, value is a primary part of the world because response to quality, or value, is what makes the world what it is. Quality is the initial stimulus. The quality event creates subjects and objects in the first place.

One way to say it: Quality has to do with our immediate participatory relation with things:

“… at the cutting edge of time, before an object can be distinguished, there must be a kind of nonintellectual awareness… You can’t be aware that you’ve seen a tree until after you’ve seen the tree… Quality is the continuing stimulus our environment puts upon us to create the world in which we live… Quality is the parent of subjects and objects. ”

Actually what Pirsig is saying here is just common sense — which is, the profound sense in which all cognition is recognition. In fact this insight was lost at the very birth of the modern age of thinking, with Descartes. He made the famous statement “I think, therefore I am” [cogito ergo sum] , as if he were the first man to wake up in the world and this was a new Genesis. Indeed this was a new world — but of cognition — not recognition. Here is announced the meeting of awareness with interiority – a truly significant moment which offered a tremendous opportunity for integration. Unfortunately the opportunity was wasted. The Spanish philosopher Ortega y Gasset remarked of Descartes that he did not really rest with the discovery of thought as a primary reality, but immediately converted it into something passive and inert — a substance – when he said “I am only a thing that thinks — “je ne suis qu’une chose qui pense” – I am a thinking thing.”

But how can thinking be a substance – the very nature of which is passive, acted upon? Thinking must be in essence alert – not inert! Descartes had the immediate insight of thinking as an activity, yet went immediately into eclipsing it, undercutting it. This is a paradox, a contradiction, at the very heart of the Modern Age.

Other critics of Descartes have noted how his cogito puts you right in the midst of an adult thinking situation. How was Descartes able to get to that place of clarity? He ignored all the historical and autobiographical steps that got him there – ignored the body, the emotion, the stumbling-over-things that leads to self-awareness. That is to say he ignored all the preceding Quality encounters. A child of three is not going to be able to express the cogito, but in terms of Pirsig, he or she would be able to say “Good!” or “More!”

“This is good!” – this is the primary quality interaction through which we are gradually able to distinguish objects in relation to our own subject, learn, remember, do metaphysics, and in general live our lives.

Or, as Pirsig puts it in more earthy fashion –“Getting drunk, picking up bar ladies and doing metaphysics is what life is all about.”

ZEN AND THE ART OF MOTORCYCLE MAINTENANCE

Now I want to back up a little and briefly outline Pirsig’s two books, to see how he arrived at his Metaphysics of Quality. Ultimately we need to address the question of if, or how, Pirsig’s discoveries matter to us, and whether these ideas can help us to live more clearly, cleanly, and fully.

Motorcycle odyssey is conceived as a kind of Chautauqua, asking the question “What is best?” In addition to the narrator and his son, there is a ghost on this trip – Phaedrus, the narrator’s earlier or former self. Phaedrus in turn is haunted by another ghost – the ghost of rationality.

Phaedrus was liquidated by court order – electroshock treatment—but his memories occasionally surface. He recollects his life as a teacher of rhetoric at the University of Montana, when he was under contract to teach “Quality” although this was never defined.

Phaedrus soon realized that there are two senses of the word Quality.

The first is excellence and worth. The second means “of what kind of something.” Concerning “of what kindness,” Owen Barfield writes in his History in English Words:

“… the more common a word is and the simpler its meaning, the bolder very likely is the original thought which it contains and the more intense the intellectual or poetic effort which went to its making. Thus, the word quality is used by most educated people… yet in order that we should have this simple word Plato had to make the tremendous effort… of turning a vague feeling into a clear thought. He invented a new word, ‘poiotes,’ ‘what-ness,’ as we might say, ‘of what kind-ness’ and Cicero translated it as qualitas….”

Note that Pirsig’s ‘quality’ has nothing to do with the “primary and secondary qualities” of later post-Enlightenment philosophy of Locke and others. Elsewhere Owen Barfield expresses the idea that is fundamental to Pirsig’s notion of Quality:

that “the dualism subjective/objective… which is fundamental neither psychologically, historically or philosophically, is an inveterate habit of thought which makes it so extraordinarily hard for the Western mind to grasp the nature of inspiration.” (Poetic Diction, 1927, p. 204)

It is the first of these characterizations of Quality – excellence or worth – that matters here, and “Inspiration” comes closest to the “Quality” Pirsig was after. He says that dividing the world between Subject and Object “shuts out Quality.” Thus, he says, “Dualistic excellence is achieved by objectivity, but creative excellence is not.”

His breakthrough moment was this. Quality is not a thing – it is an event:

Quality is the point at which subject and object meet… the event at which awareness of both subjects and objects is made possible…

Pirsig thinks there’s a “genetic defect” within Reason that keeps driving us to do what is “reasonable” even when it’s no longer good. He lays the blame for this back in ancient Greece, back to the arguments of Plato with the Sophists. According to Pirsig, the Sophists were traveling teachers of rhetoric who claimed to be able to teach virtue. This virtue, or excellence, arête— in Greek , is what Pirsig means by Quality.

Now why did Plato condemn the Sophists? Plato was developing dialectic, which is a companion of rhetoric. Dialectic means “of or pertaining to a dialogue” and it has come to have the sense of “logical argumentation.” Plato insisted that the only way you could get to the truth was through dialectic – hence he condemned the Sophists, the rhetoricians, and the poets.

But Plato also had an ideal of arête– the Good, the highest ideal to which man can strive. “All men by nature desire the Good” is the foundation of Platonic philosophy. If Plato’s Good is so close to Pirsig’s Quality, why does Phaedrus object to it so? This is where the argument becomes very subtle. Phaedrus basically says the Sophists’ idea of the good, or arête, was a living relation, that it depended on circumstances, that one should be open to it, loyally, but not blindly, like a continuing wellspring, but that Plato’s idea of the Good became encapsulated into a “Form”—

…the difference was that Plato’s Good was a fixed and unmoving Idea, whereas for the rhetoricians it was not an Idea at all. The Good was not a Form of reality. It was reality itself…

Thus Phaedrus concludes: Plato’s condemnation of the Sophists

…was part of a much larger struggle in which the reality of the Good, represented by the Sophists, and the reality of the True, represented by the dialecticians, were engaged in a huge struggle for the future mind of man. Truth won, the Good lost, and that is why today we have so little difficulty accepting the idea of truth and so much difficulty the reality of Quality, even though there is no more agreement in one area than in the other…

What was the virtue that the Sophists claimed to be able to teach?

This is the question that animates Pirsig’s sequel to ZAMM, Lila. We will turn to this book accordingly.

THE METAPHYSICS OF QUALITY – LILA

Lila takes up the story where Zen and the Art of Motorcycle Maintenance leaves off – or rather, Lilais the fictional sequel to the book that made Pirsig famous.

Lilatakes place in the setting of a boat trip down the Hudson River. The author-narrator, who often refers to himself as Phaedrus, gets involved with a young woman he meets in a bar, and one of his ongoing questions becomes: Does Lila have Quality? He says she does – and the fact that he does say this ultimately becomes important to the story. But in the course of the narrative it becomes clear to him that Lila has Biological Quality (i.e., she’s sexy). But socially and intellectually, “she’s nowhere.”

Lila’s particular quality or lack thereof form the backdrop for Pirsig’s continuing clarification of the Metaphysics of Quality. He reaches an important moment when he gains insight into the two terms: dynamic and static.

Not subject and object but dynamic and static is the basic division of reality.

Dynamic Quality is the cutting edge of life that leads to betterment, and it cannot be described or encapsulated. Almost by definition, it eludes capture; it’s the spur of the moment, the unexpected, the surprise, the gift, grace, the quantum leap, improbability, the unexpected, the sudden realization or accomplishment. There are a lot of words to describe it.

But here is an important accompanying insight: life cannot exist on pure Dynamic Quality alone.

This is the way he puts it:

Without Dynamic Quality the organism cannot grow. Without static quality the organism cannot last. Both are needed.

This is the germinal idea that leads him to a new understanding of evolution, which is not just a forward movement. Rather, every dynamic advance has to be followed by a stabilizing hold or “static latch.”

Unless the dynamic movement forward can be encapsulated by the static latch, the gain will not be permanent, and deterioration or reversion will set in. In the history of life this dynamic-static conversation can be seen in how the static molecule, protein, surrounds and protects the dynamic DNA. All biological and higher forms show this static-dynamic pattern, from semi-permeable cell walls that protect the dynamic interior process of the cell to “bones, shell, hide, fur, burrows, clothes, houses, villages, castles, rituals, symbols, laws, and libraries. All of these prevent evolutionary degeneration.”

With this insight he has undercut the materialism from the Darwinian evolutionary idea and freed it to become a usefully (dynamic) concept. Life is the response to Quality, on whatever level of discourse it may be. And human society, too, can be understood in a new and non-reductive way as a taking account of static and dynamic quality.

With the division of static quality into four components: inorganic, biological, social and intellectual, the Metaphysics of Quality becomes a comprehensive tool for analysis and understanding.

Let us look at how Pirsig uses this tool in his social analysis.

PIRSIG’S SOCIAL ANALYSIS

One of the most useful parts of Lila to me is Pirsig’s social analysis. He says that the Victorian era was the last period in which social values were more important than intellectual ones. “Intellectuals were expected to decorate the social parade, not lead it.” This changed with the 20th century with the election of Woodrow Wilson and later, the period of the New Deal.

Until World War I: Dominance of Victorian social values.

World War I – World War II: dominance of intellectuals

World War II until the 1970’s: continuing dominance of intellectuals but with increasing challenge from “Hippies” – those who rejected both social and intellectual values

From 1970’s—- present: rise of neocons (a kind of pseudo-Victorian moral posture with increased militarism), society drifting back into its last static latch, which for us is becoming a static prison

Pirsig writes:

The Hippie rejection of social and intellectual patterns left just two directions to go: toward biological quality and toward Dynamic Quality. The revolutionaries of the 60s thought that since both are anti-social, and since both are anti-intellectual, why then they must both be the same. This was the mistake.

Phaedrus says he once made the same mistake, but the Metaphysics of Quality helped him clear it up.

When biological quality and Dynamic Quality are confused, the result isn’t an increase in Dynamic Quality. It’s an extremely destructive form of degeneracy of the sort seen in the Manson murders, the Jonestown madness, and the increase in crime and drug addiction throughout the country.

The result of the failures of the intellectual revolution and the hippie revolution was that society is sinking into an “intellectual, social and economic rust-belt” and seems to have given up on dynamic quality. He summarizes that:

The paralysis of America is a paralysis of moral patterns…

When subject/object metaphysics declared morals off-limits, amoral objectivity came to reign supreme. It condemns social repression as the enemy of liberty, but has never come up with a single principle to distinguish a genuine freedom fighter combating social repression from a common criminal fighting social repression. [Example: Norman Mailer’s book on Gary Gilmore.] Instead, it has championed both. The result is an increasingly chaotic social confusion.

This confusion lies very deep in the fabric of American life and I think is the true source of the so-called War on Terror. Citizens are being treated like criminals because we have never, as a society, understood the nature of the social. When we think about the social we either get conformity, or we get the idea of the heroic rebel fighting repression. But what about the intermediate realm, the civic or civil, where most of us live most of the time? This is the area we have neglected. Thus, Pirsig says:

The paralysis of America is a paralysis of moral patterns.

Why has America given up on space exploration, for instance, and instead, seems to be bent on reinventing the wheel with regard to marriage and sexuality? Our society appears to have given up on dynamic quality and has become fearful, fussy, sterile and sanctimonious – with ignorant and self-righteous bozos in office who don’t take the trouble to learn a foreign language or even familiarize themselves with history of the countries in which they feel entitled to meddle.

Let’s stop obsessing about EQUALITY and start going for QUALITY! Let us stop allowing our moral values to be twisted and our story as a people to be distorted. Let us affirm the necessity of thinking cleanly, clearly, with honor and honesty, and start to make America live up to the ideal that we all cherish.

Thank you.

Caryl Johnston

![bigstockphoto_Black_Flowers_4800530[1] bigstockphoto_Black_Flowers_4800530[1]](https://www.thinkinghousewife.com/wp/wp-content/uploads/2011/03/bigstockphoto_Black_Flowers_480053013-150x105.jpg)

— Comments —

John P. writes:

This is a fascinating lecture on Robert Pirsig, an author I am aware of but have never read. Thank you for posting it. There’s a lot to ponder here and I may have other thoughts as I chew on it but I did want to make one observation.

Caryl Johnston says, “In my view, our deteriorating national situation is ultimately owing to the decline of thinking…”. Perhaps it’s the materialist in me speaking but I have my doubts that thinking would mysteriously decline in the absence of a concerted attack on thinking. And in that context I would ask the age old question “Cui Bono?”

Julien Benda, in his 1927 book La Trahison des Clercs (Treason of the Learned) argues that intellectuals had lost the capacity for dispassionate reason and defended Classical Civilisation and Christian tradition. I would extend and modify his argument and describe a kind of ‘intellectual coup d’etat’ in which intellectuals have acted, by and large, to extend their influence in society and the state by deprecating all traditional frames of reference. This, at one and the same time, increases the reliance of society on intellectuals and scientism while inducing a degeneration of common sense and homiletic guides to action. Needless to say I don’t view this as a conspiracy but rather as an unconscious manifestation of the otherwise thwarted will to power of intellectuals, who held less influence under the old scheme of society.

Laura writes:

Intellectuals have gone from servants of the common good to debunkers of it.

I have never read Pirsig’s book either. I enjoyed Caryl’s reflections very much. The first question that came to mind was, how does a culture arrive at quality in moral and civic life if there is no religious consensus to define it?

If one embraces the idea of quality in marriage, what is that? Does quality consist of the sentiment between two people, as advocates of same-sex marriage and easy divorce would argue, or is it found in the pursuit of spiritual ideals and an unspoken contract between the generations?

Jeff W. writes:

When discussing how America might revive itself, I often think of a theory of the cycle of history. It goes:

Bondage to Spiritual Faith;

Spiritual Faith to Courage;

Courage to Freedom;

Freedom to Abundance;

Abundance to Selfishness;

Selfishness to Complacency;

Complacency to Apathy;

Apathy to Fear;

Fear to Dependency;

Dependency to Bondage

In 1946, when Henning Prentis, president of Armstrong Cork Co., described this cycle in a speech in Montreal, he also said, “In the United States we stand today at the complacency-apathy stage.”

In 2011, I say we are now at the dependency-bondage stage. Everyone wants to be dependent on government. Even the Tea Party people are adamant that their Medicare and Social Security benefits must be paid in full. Indeed that is what much of the Tea Party demonstrations have been all about.

Americans sink deeper into bondage each year. We are in bondage to Middle East dictators for our basic fuel supplies. We are tax slaves to corrupt government and forced-labor slaves to government schools. Most Americans are sinking ever deeper into debt slavery to the banks. Americans even allow their communications to be policed for violations of political correctness. In 2011 Americans are now basically slaves, and it is bound to get worse. Those who have the courage to stand up for freedom are simply too few.

But after great suffering, and probably great loss of life, like the Phoenix rising from the ashes, spiritual faith, I believe, will return. But things will have to get a lot worse before they get better.

Peter S. writes:

On the matter of the baleful domination of intellectual in the modern era, one might peruse with benefit Paul Johnson’s Intellectuals: From Marx and Tolstoy to Sartre and Chomsky and Thomas Sowell’s Intellectuals and Society; Roger Kimball’s Lives of the Mind: The Use and Abuse of Intelligence from Hegel to Wodehouse and Richard Posner’s Public Intellectuals: A Study of Decline might also be considered.

Markus writes:

I second Peter S.’s recommendation of Intellectuals by Paul Johnson. Fascinating — and occasionally terrifying — short bios of some of the leading lights of the post-englightenment world.

Another good one for a traditionalist understanding of our modern world is Chirstopher Lasch’s excellent book The True and Only Heaven: Progress and its Critics.

Caryl Johnston writes:

Thanks to all the folks who wrote in with the comments. Laura’s point, how do you arrive at civic quality without religious consensus, hits the target exactly. This is why I thought Pirsig’s outline of the fourfold structure of static quality was so useful: it allows us to make distinctions between biological, social and intellectual quality and to maintain a scale of values.

I am not sure, though, whether even Pirsig’s useful distinctions would assist us in opposing the radical de-gendering (social engineering) of society that is now going on. It is important to recall that Pirsig’s “Quality” has to do with the mind’s contact with real experience – that is the first step. The main characteristic of modernism is that the mind is, so to speak, in love with itself, its own thinking

process – which is to say that ideology trumps experience every time. Thus modernity is inherently revolutionary, because it is as if the world has to conform to my thought.

So, the first thing to remember about the “Metaphysics of Quality” is that it puts the mind, that is thinking, back into a dialogical, mutal relationship with the world – instead of the position of arrogant lordship. We are beginning to see the consequences of this arrogance. The question is, will we see it for what it is? And will we survive the ecological and other catastrophes we are unleashing?

Laura writes:

That’s an excellent point. How can one even reach people so radically cut off from the real world except by first drawing attention to the fact that they are radically cut off from the real world because they worship idea? How does one talk to someone who says two “mothers” are no different from a mother and father? Sense and sensibility are utterly divorced. Yes, the mind is in love with itself – and also cut off from itself.

I am assuming Caryl means that Pirsig puts the mind back into relationship with the world by drawing attention to the quality of external realities. He says, “Think. But think of what is beyond the self. Look and examine what is before you as it is.” Metaphysics is not creation but observation.

Caryl responds:

Thanks for your reply. I would define “Quality” as the immediate participatory relationship with things. The “quality of” something is another thing altogether, and Pirsig was careful to make this distinction. I wouldn’t go so far as to say that “metaphysics is not creation but observation,” but I do think that metaphysics involves observing one’s own thoughts and ideas. It does seem to be true that our ideas make the difference in the degree of participation (and understanding) we are able to have.

Laura writes:

In other words, as you quoted Pirsig above,

Not subject and object but dynamic and static is the basic division of reality.

You also wrote,

But here is an important accompanying insight: life cannot exist on pure Dynamic Quality alone.

This reminds me of Father Seraphim Rose and his description of the third phase of nihilism as consisting of Vitalism, or the worship of energy.