Khrushchev Comes to Chester

June 9, 2015

HERE is the latest installment in the ongoing series, “Tales of Chester,” a first-hand account of my husband’s childhood in the industrial — and strategically-vital — town of Chester, Pennsylvania.

The End of the World

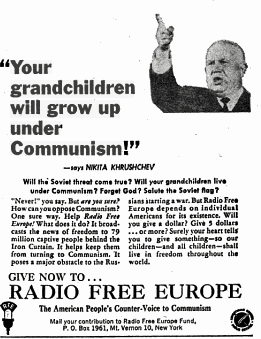

We were not surprised to learn that the living Satan himself had added the strategically-vital town of Chester, Pennsylvania, to his itinerary. Chester was home to one of the world’s great shipyards and would be a magnet for Russian atomic bombs. So it only made sense that the great conqueror and oppressor and hater of all that was holy, Nikita Khrushchev, would want to see this inviting target firsthand when he visited the United States.

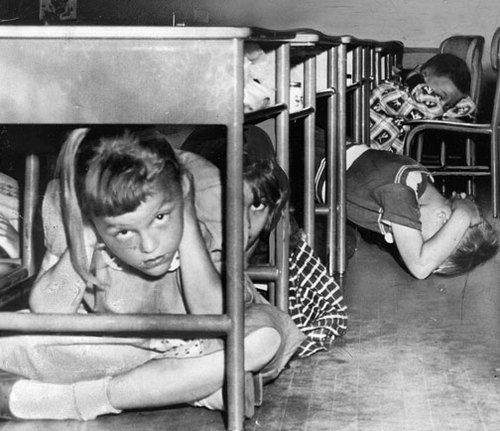

The buildup to Khrushchev’s visit to America evoked images as threatening as a gathering of thunderheads along a storm front, the way we imagined the sky might look when Gabriel sounded the trumpet to wake the dead at the end of world. Normally, the Chester Times devoted its pages to Iocal Republican politics (the only kind we had) or the exploits of fullbacks at St. James and the basketball superstars at Chester High, the only kind of kids worth a damn in this town. These were extreme times, however. In the summer of 1959, on the eve of Khrushchev’s visit, the paper rolled out an extensive series under the headline, “We Will Bury You!” It was described as the Communist “Blueprint for the Future,” and we had every reason to believe the Russians could execute to the letter their plans for world domination.

Two days before Khrushchev set foot in California, a Russian rocket reached the moon. Damned if they hadn’t embarrassed us once again, and if they were this far ahead in the space race, how much further were they ahead in the weapons race? If he wanted to raise our anxiety levels to the maximum threshold, Khrushchev could not have timed his visit more exquisitely. We half-expected him to call a press conference to announce the end of the world.

For the world was going to end. This I knew because my brother had calmly informed me of this on an October night two years before, when I was eight years old.

I was taking a bath, which was something of a project in our household. Like any self-respecting boy of eight, I found the idea of a bath revolting — until I actually got into the tub, at which point I came to luxuriate anew in the pleasures of immersion in hot water that would wrinkle the skin into elephantine folds. In our house, you could stay in the porcelain tub supported on lion’s feet and savor the endless distortions of the contours of your fingertips as long as you desired. If you didn’t mind company. We had one bathroom for nine people: parents, five offspring and two roomers. While taking a bath, my brothers and sister would come and go as they found necessary. On this particular night, my brother Jim came into the bathroom to brush his teeth. He was looking in the mirror, not at me or my endlessly folded skin, when he said casually:

“The world is going to end in 1960.”

How did he know, I asked.

“Haven’t you heard about the Letter?”

No, I hadn’t.

To older brothers, younger brothers are an endless source of exasperation, embarrassment and irritation. To younger brothers, older brothers are important sources of information, more so than teachers or parents. Older brothers tend to tell you things that matter. He patiently explained that the Blessed Mother had appeared to three peasant children in Fatima, Portugal, back in October 1917. I was familiar with that part. I had not known, however, about the Letter she had given the children to deliver to the Pope with strict orders that it was not to be opened until 1960.

No one knew the contents of this letter, although given the state of the world, the obvious conclusion was that it dealt very specifically with its limited future. In all likelihood, by my brother’s unassailable reasoning, once the Letter was opened, Gabriel would sound the trumpet, flames would leap into the blackened sky and the Last Judgment would commence.

When Sister confirmed that my brother’s report was accurate, no news could have been more disconcerting, short of being told you had polio or that school would now extend through the summer. In an era of maximum feasible anxiety, the mysterious Letter and its chilling possibilities moved to the foreground of unspeakable fears. Roman Catholic history was rich with accounts of apparitions and supernatural occurrences from Damascus to Lourdes, yet this I was told was the first case of Divine written instruction since Moses had emerged dazed, disheveled and exhausted from the summit of Sinai. We had learned of the fate of Sodom and Gomorrah, and now we were left to wonder whether the Letter was the official announcement that the entire world would be taught the same lesson. Something had gone so wrong on Earth that God had dispatched His Own Mother to deliver warnings in person.

What we knew of the couriers of the message gave the accounts of the visions unassailable credibility. Not that we needed proof: Sister said it therefore it was true. The three were children, like us: Jacinta, Lucy and Francisco, honest and pious children of steadfast faith. Children of integrity. True children of God. The only kind of human beings who could be entrusted with delivering messages from the Almighty. Interviewed separately, they held to the same accounts of what had happened, even when the interrogators threatened to boil them in oil, so we were told.

Their accounts were full of stunning, prescient detail from the Blessed Mother, information far too sophisticated to have originated in the prosaic imaginations of peasant children. Mary had told them that World War I would end and that a far deadlier war would follow. More amazingly, she informed the children that the greatest threat to world peace and Christianity was godless Communism, something no one could have imagined in 1917. How could anyone but the Mother of God have been aware of such a world menace so far back in time? These details provided overwhelmingly compelling evidence for the veracity of the miracle. If any doubt remained, it was routed by the existence of the physical evidence: the Letter, now in the custody of the Pope.

In the four decades after Fatima, events unfolded just as Our Lady had predicted. The Communists were everything she had warned us about. They had taken over eastern Europe, China and North Korea. Where would this stop?

I did not fully understand the intricacies of world events. I did know enough to understand that the world was in deep trouble and on the brink of a war unlike any in history. I came to fear the news. I could not avoid hearing the word “Soviet,” not knowing fully what a Soviet was, only that it was something exotic and dangerous, that a Soviet was an enemy who wanted to kill us and that once a war started the human race would not be long for this earth. As best as I could determine, the United States and these Soviets had two fundamental differences. They wanted to conquer the world, and we didn’t. They didn’t believe in God, and we did.

Our faith in God gave us hope that we would prevail against this horrible threat, and weren’t we living in the greatest nation in human history? Had we never lost a war? Wasn’t our technology the envy of the world? What did we have to worry about?

On one of those mystical mornings, only a few days after my brother had given me his chilling briefing on Fatima, we awoke to a shocking realization. The Russians were smarter than us, and they were ahead of us. A Russian space satellite with the frightening name “Sputnik” was orbiting the Earth. We heard on radio that if we looked to the sky, we could see it as a red blinking light. My mother sent me to the store that morning in the near-darkness. I thought I saw a light blinking in the pre-dawn sky. If the Russians could do this— launch a satellite into outer space — how easily could they launch atomic bombs right at the shipyard where my father worked? As far as we could tell, Sputnik was a Russian word for panic. My sister told me that Russia was so far ahead because the government forced kids to become scientists, and that if I were in Russia I’d be wearing a white lab coat and thick glasses. I did not want to become a scientist. I wanted to be a baseball player.

Humans, particularly children, have an extraordinary capacity to adapt and accept absurd and even terrifying circumstances while keeping their more banal anxieties in the foreground. In 1959, as the day of the Great Letter Opening drew closer, an event challenged that capacity as much as anything since Sputnik. At the beginning of the year we knew something big had happened in Cuba, which, until then, we knew primarily as the birthplace of Desi Arnaz. At first, we were led to believe it was a benign development: A bad government and a tyrant had been overthrown. To our absolute horror, however, within weeks we learned that the new leader, a dirty, bearded cigar-smoker, was in reality a Communist — and a former altar boy at that! Now we had a Communist country 90 miles from the United States. The Communists were this close to us, and they were brainwashing former Catholics! They were intent on taking over the world, just as the Blessed Mother had warned before anyone had any idea who they were.

It was into this background that the graceless man behind the Iron Curtain inserted his eerie silhouette in 1959. Two days before Nikita Khrushchev arrived, a Soviet satellite landed on the moon, an event as foreboding as distant thunder announcing the arrival of a storm. They were ahead, and they were going to bury us. Khrushchev was a messenger of doom straight from central casting. He had an impersonal moon face, expressionless except when he flew into a rage or angrily reminded us that it was useless to resist the inevitable consequences of Soviet superiority. He had bad teeth, something we did not see in American politicians. Any man who didn’t give a damn about such personal details couldn’t give a damn about people he didn’t know.

He threw public temper tantrums, which is something else we never saw in our own politicians. He was bitter because he wasn’t allowed to visit Disneyland. Disneyland!? Was he planning to hunt down children so that he could shave their heads and wrap their skulls in chains?

Khrushchev did indeed visit Chester. He passed through on a train on his way from Washington to New York. It was plenty of time for him to scope out our weaknesses and size up our defenses. We were somewhat flattered. He realized our importance to the nation. But we were glad he didn’t step foot in our town.

It was an immense relief when the man who would bury us returned to Moscow, even though there remained that minor detail that the end truly was near. The days were getting shorter, and the mornings ever darker. The end of October always was a scary period. Since we still were on daylight-saving time, we would not see the first light of day until we had left for school, the malingering darkness adding a curtain of fright to our morning walks to church and school. The waning days of October 1959 were especially frightful because we were creeping toward the inevitable day that the letter would he opened. It was all so scary that I stopped noticing that Renner’s house had become a ruined hulk.

Jan. 1, 1960: the first day that the contents of the letter of Fatima could have been revealed, passed without a word from the Pope. The next 30 days passed and then the 29 days of February with no word from the Vatican. A rumor flashed through the school that the Pope had opened the letter, read the contents and passed out. Whether this actually happened and whether the Pope was revived, we did not find out. As the year went on, the Letter ceased to be the subject of rumor, or even conversation. No one brought it up. Sister never mentioned it. Nor did my brothers, nor did anyone on the Corner or at school. Had everyone forgotten, or was everyone avoiding the unmentionable?

By the time school let out fur the summer, interest in the Letter resurfaced. The popular rumor about the Pope’s fainting spell was replaced by a fresh one, which might well have been inspired by wishful thinking. John Kennedy was running for president, and he actually had an excellent chance of winning. This was an astonishing development. He had been an obscure figure, quite young and inexperienced, and most stunningly of all, a Roman Catholic.

In the previous summer, two months before Khrushchev’s visit, our uncle from Massachusetts was making his annual visit to our house. He and my mother and father and assorted aunts and uncles were gathered around our dining room table discussing politics and all agreeing what a shame it was that Eisenhower couldn’t stay in power, given the dangerous state of the world. Since he was from so far away, I believed that my once knew all things. I had heard of this man Kennedy, and I asked my uncle if Kennedy automatically would become president when Eisenhower quit.

They all laughed.

By June 1960, six months into the year of the letter, Kennedy had become the likely Democratic presidential nominee. Two months before, he thumped Hubert Humphrey, an old, bald guy who drank coffee from a Styrofoam cup, in the Wisconsin primary. That was in the state right next door to Humphrey’s. A month later, he won a more-improbable victory in West Virginia- a state infested with Protestant infidels. His successes had a profound and wholly positive impact on the Catholic youth of America, not only as a source of inspiration but in the manner in which it changed the speculation about the Letter of Fatima.

No longer was the world going to end. No longer was the Pope opening the letter and passing out. According to the latest rumor, the later informed the world that a Ronan Catholic would be elected President of the United States. It was an attractive hypothesis. We all wanted Kennedy to win. He was young and good-looking with nice teeth and a handsome wife, as opposed to his sinister-looking Republican opponent with the Satanic beard shadow and evil-sounding name, Nixon, which sounded forebodingly like Nikita. Kennedy’s election would qualify as an out-and-out miracle. No one believed in 1960 that a Catholic could become president. And to think that this message about a distant election in a distant country would have hen delivered by the Blessed Mother way back in 1917 in the tiny village of Fatima, Portugal, in the very year that John Kennedy was born! Only the Creator of the universe could have foreseen such an extraordinary evolution of circumstance that would deliver a Catholic to the White House to confront the atheistic threat now spreading across the world. It all made sense now. This latest speculation about the Letter’s contents was a compelling one. It also was an attractive one, since it the living Hell out of the alternatives.

On election night, we went to church, came home, ate bacon sandwiches on toast and watched the returns. Kennedy did win the election. It was improbably close, and the outcome wasn’t certain until the following morning. The morning paper declared Kennedy the winner, but Sister said the paper had been wrong about Dewey and Truman. The headline in the afternoon paper read, “Se. Kennedy leads.” Kennedy’s victory wasn’t assured until Illinois went into his column. It was the closest race in history, just as my mother had predicted. Whether all these circumstances were detailed in the letter remained a secret. No announcement came from the Vatican. The Electoral College certified Kennedy’s win in December, still without an announcement from the Vatican. The Pope said nothing about the Letter for the rest of the year. Whatever the contents of the Letter, we had survived 1960.

Not even a snowfall in April has a shorter life than a 12-year-old’s attention span. The Letter of Fatima receded from our consciousness until it evaporated. The fear of the Letter went the way of other childhood anxieties that burrow into inaccessible regions of memory so that the mind can make room for fresh anxieties and children can get on with the challenging business of becoming teenagers.

The world did not end in 1961, a year that began on a fortuitous note with John Kennedy’s inauguration. It was one of the happiest days of our lives because it snowed over a foot and school was closed. He walked down Pennsylvania Avenue without a coat or hat, and a quivering old man with a moist nose read a poem. We had heard something about a “Bay of Pigs” invasion of Cuba and the construction of the Berlin Wall, but these crises were too esoteric for the average Chester teenager. The Russians sent a cosmonaut, Yuri Gargarin, into orbit to remind us again of their technological superiority. But being neither old, nor bald, nor boring, Kennedy and his enigmatic and attractive wife were able to draw more attention to themselves than the state of the world. That was the great success of Kennedy’s first year in office. We paid far more attention to his peculiar accent and her odd clothing and her “tour of the White House” than the Cold War.

On the night of October 22, 1962, that all changed for us with the chilling abruptness of an unanticipated early frost. We learned that night that the United States had discovered missiles in Cuba. We all watched Kennedy on television. When the President spoke, he was on every channel, and no one would want to miss this speech. I can’t say that I understood fully what he was saying. He used big words and spoke elliptically, yet it was clear that something terrifying was unfolding. I went to consult with Mrs. Weir, our next-door neighbor for reassurance. As soon as she opened her door, she said, “We’re going to war.” I protested that Kennedy hadn’t said that exactly, at least in the parts of the speech that I could comprehend. I heard him mention “offensive” weapons and say that the United States would set up a quarantine, although I wasn’t sure what that was, around Cuba.

“We’re going to war.”

For my generation, the next 36 hours represented the scariest period of our lives. The “quarantine” was a fancy word for a naval blockade, that much was obvious even to the youth of Chester. We assumed that the war would start when the Soviet ships encountered the blockade. Perhaps the first missiles already had already been launched, and Chester was next.

It could be unnerving living so close to the airport. All day and all night we heard low-flying planes taking off or coming in for landings, so loud they sounded as though they were about to crash into the house. Ordinarily, the noise was a mere nuisance. After Kennedy’s speech, it became a chronic source of terror. The next engine we heard could be that of a Soviet bomber heading for the shipyard. The Soviets were fanatical; would they have Kamikaze pilots?

On Tuesday, we heard nothing from Washington or Moscow, for which we were grateful. Wednesday passed with no sign of either side having launched a missile, and the unbearably long week quietly crept into Thursday.

The quiet was shattered that day, not in Washington or Moscow, but in New York. At the U.N., Adlai Stevenson, little more than a man with an alien name to kids our age, publicly challenged the Soviet delegate. He asked if the Russians had missiles in Cuba, and said the United States was prepared to wait until “Hell freezes over” for an answer. It was quite an image to use among atheists, but it had a reassuring power, force and confidence. The Soviet delegate clearly was nonplussed and utterly unprepared to respond to such a confrontational question. He adjusted his headpiece. He attempted to affect a perplexity, as if wondering whether he had misheard the question from this mild-mannered gentleman or whether it had been translated improperly. He appeared confused, even nervous. We were standing up to the godless heathens; they were scared.

We still had heard nothing about the confrontation between the American and Soviet ships, and that night we found out why. There had been no confrontation. The news was too good to be true. The Soviet ships heading toward Cuba turned back! Incredibly, within days, the Soviets actually agreed to take all of their missiles out of Cuba. The world had averted a war that had appeared all but certain. It was a miraculous sequence of events.

Was this the miracle cataloged in the letter of Fatima? It is a question no one had asked during or after the Cuban missile crisis. Not once did such speculation make an appearance even in the very, very backs of our minds. Speculation over the contents of the letter had ceased altogether. By 1962, the Letter that had been a daily obsession was no longer a part of our consciousness.

Cuba had elevated the threshold of fright to a level with which subsequent events could not compete. It marked the peak of the Cold War, and nothing that followed matched that degree of brinksmanship. Nothing generated the same intensity of fright. The Kennedy assassination engendered a short-lived anxiety, but we were quickly assured that the assassin was a loser loner with no real connection with the Soviet government. After the first wave of shock subsided, Lyndon Johnson quickly became a safe figure, albeit a less-attractive one. We were amused by his accent, by his pulling his dog’s ears, by his showing his surgical scar to photographers, by the stories of his driving around Texas at 90 m.p.h. and throwing beer cans out the car window. He had a wife with a bizarre name, “Lady Bird,” and an elongated neck, but she was no Jackie. We were settling into a duller and safer time. The fear of nuclear war was going the way of the anxiety over the Letter of Fatima.

One languid afternoon in October 1964, Brother Mahoney was discussing the subtleties of sin. Brother Mahoney was a beefy man with muscular arms who had a biting wit and a formidable presence that instilled fear in teenagers, a power reinforced by occasional flashes of temper. If he caught anyone chewing gum, he would force the chewer to stand in front of the class and attempt to whistle while chewing on six saltines. If he caught a student talking in class, the offender would be conscripted to join Mike Mahoney’s Air Force in which the perpetrator would report to his classroom after school and stand at attention with arms spread for an indefinite period, two textbooks placed atop each outstretched hand.

For a man with such an impressive behavior-control arsenal, Brother Mahoney did tolerate a certain inattention. He well knew that his subject, “religion,” was an ambiguous one. He held the official curriculum in disdain. He knew our circumstances. We were, after all, teenagers. We had his period after lunch. When the weather was warm, the classroom was roasting. The combination of the heat and full stomachs could induce narcolepsy.

Such a set of circumstances aligned on this particular afternoon, when Brother Mahoney was elaborating on the “mitigating circumstances” under which a sin might not be a sin. That was what I remembered on a day in which the impalpable world of sleep was irresistible. I recall my chin resting upon my jaw, the jaw periodically slipping off the fist and jarring me awake with a buzzing sound, as though an electrical charge was being applied to the back of my head. While navigating among varying degrees of wakefulness, I became aware of the raised hand of a classmate and a startling question utterly out of time and context. Had he, too, been asleep?

Whatever happened, George Kennedy wanted to know, to the Letter of Fatima, or was it Fantasmagoria?

Was the question from a dream? Brother Mahoney said nothing for several seconds. We were trying to re-focus on a concept and a place that had once been so imprinted in our consciousness, as though shaking off a spell of mass hypnosis. It was coming back to us. Perhaps Brother Mahoney was going through the same processes during the silence. Yes, this was a more urgent and interesting topic than sin and its mitigating circumstances.

“What about it?” Brother Mahoney finally asked.

“What happened to it?” George persisted.

“What do you mean what happened to it?”

“Wasn’t the Pope supposed to open it in 1960?”

“Yes?”

“So what did the letter say?”

“I don’t think I understand the question.”

“The Pope was supposed to open the letter, but …”

“Wait a minute,” Brother interrupted. “The Blessed Mother gave instructions to open the letter in 1960, correct?”

“That’s right.”

“The Blessed Mother never said anything about making the contents public.”

No one wanted to test Mike Mahoney’s patience on a matter that he felt to be so clear-cut and not meriting of further discussions. Just like that, the subject was dropped for the last time.

We stopped thinking about the end of the world.

The air-raid drills ceased, as did the testings of the air-raid sirens. Khrushchev, himself, became an ever-more remote figure, as vague as he was on the day that he passed through the strategically-vital town of Chester, Pa.

We had all gone to the train station on the afternoon of September 27, 1959 to wave to the train bearing the Soviet premier from Washington to New York.

It whizzed through Chester at 100 m.p.h., passing the “What Chester Makes, Makes Chester” on the electric company building and the gigantic likeness of the Scott toilet-paper roll, stirring the dust and debris of the platform. We were waving goodbye.