A Song, a Bar and a Ballroom

April 13, 2016

ALAN writes:

Late one afternoon or early evening many years ago, I was walking along a street in downtown St. Louis when I happened to walk past a bar. It was not my destination at that moment and I did not go in. But the door was open and as I walked past it, I heard the unmistakable sound of the song “Careless” floating out of the bar. At that instant I felt a kinship with the bartender and the people in that bar. They were likely of an age to remember songs like “Careless” from when they were introduced years ago and to have grown up with a scale of values that enabled them to understand and appreciate such ballads. People who enjoyed a classic, sentimental old song like “Careless” were my kind of people.

I never went into that bar, then or afterward, but it was one of those moments that remain imprinted forever in one’s memory.

“Careless” was recorded by bandleader Eddy Howard years before I was born. I dare say no readers of The Thinking Housewife would recognize his name. But his orchestra and recordings were very popular in the 1940s-‘50s, especially in the Midwest. Big Band historian George T. Simon wrote of Eddy Howard: He “had the cheery, pink-cheeked vanilla appearance one might expect of a clerk in a country store—but he sang with tremendous warmth and expression.” [George T. Simon, The Big Bands, Macmillan, 1971, p. 281 ]

Indeed he did. That was one reason why my father enjoyed Eddy Howard’s music. His voice and manner of singing were so soothing. “Careless” is a good example of that, as is “To Each His Own”. To hear Eddy Howard sing such ballads is to be transported to a more serene place.

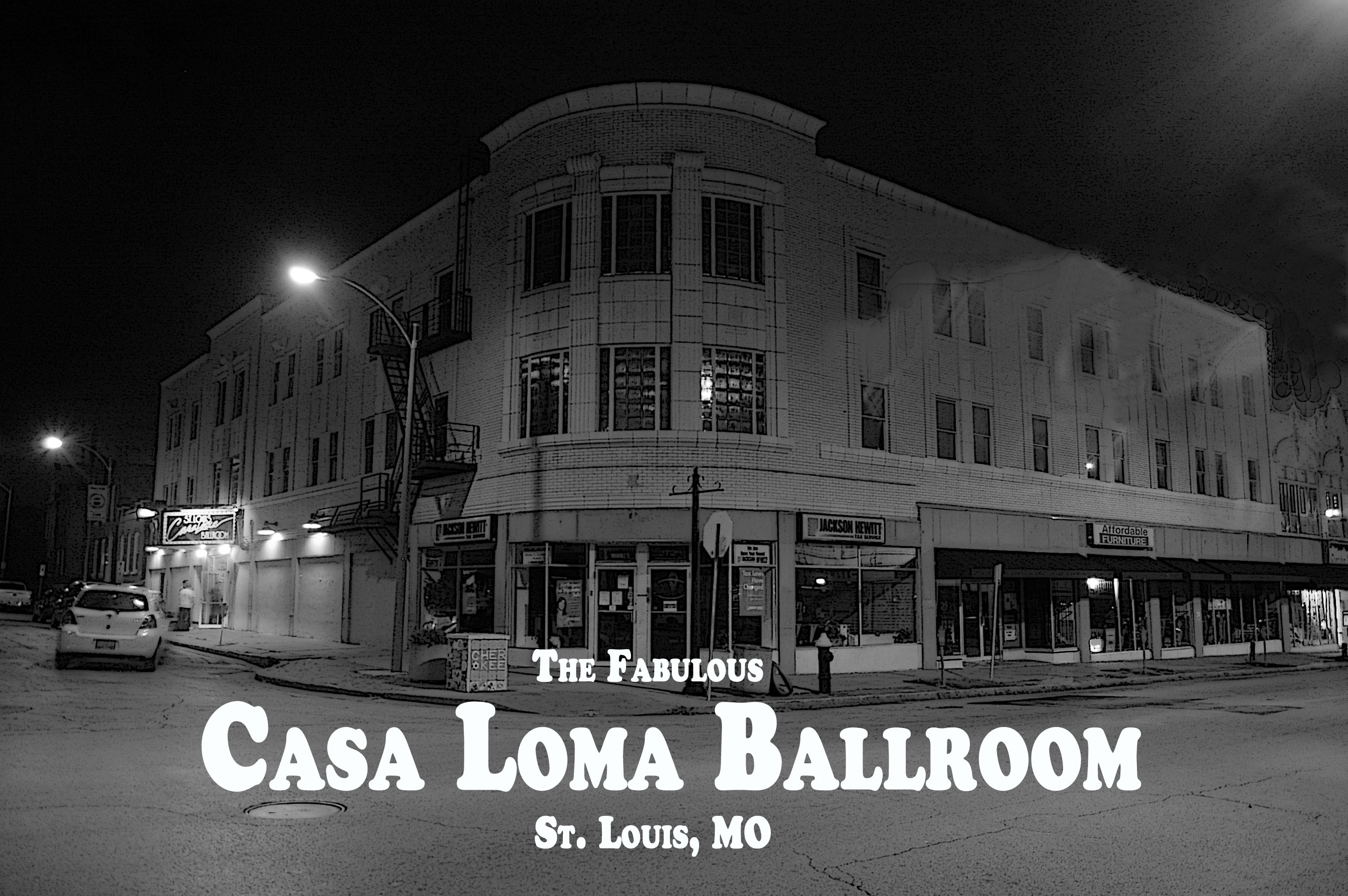

Eddy Howard and his orchestra made their first professional appearance at the Casa Loma Ballroom in south St. Louis in 1941. For all I know, my father may have been in the audience that evening or at one or more of the other eight engagements that Eddy Howard played at that ballroom between 1941 and 1955. I grew up in a house within walking distance of that ballroom. Its hierarchy of virtues included gracious manners and carriage, and standards of proper conduct were enforced at all dances. Among many other entertainers who appeared there in the 1940s-‘50s were Dinah Shore, Tommy and Jimmy Dorsey, Harry James, Tony Bennett, the King Sisters, Teresa Brewer, Guy Lombardo, and Lawrence Welk.

The Casa Loma Ballroom lived for 55 years. Its closing in 1990 prompted many older people to recall fond memories of dancing there in the 1940s.

The Casa Loma “was the best thing that happened to St. Louis,” one woman wrote to a local newspaper. “I started going there in 1941. They always had terrific bands there. There was no place like it….”

Another woman wrote: “The Casa Loma days were the best days of my life. In 1941-’42, we enjoyed Eddy Howard, Dick Jurgens, Stan Kenton, and many more that played there. It was a wonderful place to go.”

And a third woman wrote: “One of my memories was when I met Lawrence Welk at the Casa Loma. He used to get on the dance floor and dance with the different girls, and I was one of them. He was a very good dancer and friendly. ……Wonderful memories.”

My father had a wealth of such memories because he attended many dances there in the 1940s. In his retirement years, he spent many hours reading microfilmed newspapers to compile a list of all the musicians and singers who performed at the Casa Loma in the 1930s-‘50s. He remembered it as a clean, well-kept, beautiful ballroom. He carried a lifetime of memories with him when he paid a last visit to that building shortly after the ballroom closed. In a brief remembrance, he wrote: “It is hard to say goodbye to an old friend.”

A long-playing record album released in 1978 features a cover photograph of Eddy Howard and his orchestra at Elitch’s Gardens in Denver in 1947: Fourteen white men, all of them well-groomed in jacket, white shirt, and tie; no blue jeans, no long hair, no beards, no expression of arrogant conceit or defiance; a group of men who were in business not to help advance a revolution but to provide an evening of musical serenity for Americans who enjoyed dancing and were happy just to be alive and safe in the aftermath of World War II.

[ The photograph can be seen here.]

Sixty-one years after that photograph was taken, the daughter of one of those musicians wrote:

“My father is on the cover, front row left. Tom Martin, tenor sax. Eddy Howard played music to dance to with someone you loved. He had a beautiful voice. These songs are wonderful. Listen to them and you will be transported to another time. Before TV, when people went out dancing for their entertainment. I knew most of the men in this picture, they were great guys, friends with each other who loved to make music. We are lucky that this music is still available.”

[Jill Martin, comments at Amazon.com, Aug. 30, 2008 ]

Years after the day I walked past that bar, I was looking through a box of newspaper clippings when I found an article about that bar written by a newspaper reporter who, like me, grew up in a Catholic family in south St. Louis. He wrote: Fahey’s Bar “is a quiet bar. Leather booths line the wall…. Chandeliers make for quiet conversation at the bar…. It is not for television watchers or lovers of loud music….”

The owner-bartender made a point of not permitting loud music or profanity. “They’re using language in the movies today that I won’t let them use in my saloon,” he said. “If they can’t talk any better than that, I tell them to get out.”

[Raymond Vodicka, “Downtown Neighborhood Bar”, St. Louis Post-Dispatch, March 3, 1978 ]

Imagine that, if you can: A bar where quiet conversation was possible, a bar whose owner would not lower his standards, a bar for grown-ups….my kind of bar.

Compare that moral-esthetic standard with the sloppy apparel, disheveled appearance, and surly attitude projected by rock bands whose “music” is blasted at ear-splitting volume in today’s trendy “sports bars” for people who have never known anything better. If the owners of such bars instructed customers who use profanity to get out, would they have any customers left? If they turned off the loud “music” and video screens, would any of their customers know how to talk in quiet conversation?

Before he formed his own band, Eddy Howard worked as a vocalist in the Dick Jurgens band. Another vocalist-musician in that band was a man named Buddy Moreno. The three men became friends. That was in the 1930s.

It was forty years later that I first heard Eddy Howard’s “Careless” on St. Louis radio station WEW, whose program director was Buddy Moreno—the same Buddy Moreno who had known and worked with Eddy Howard and had since made his home near St. Louis. The station’s record library and studio were in an unpretentious, old brick building less than half a mile from where my father lived. We walked past it often.

Like Lawrence Auster (who was my age), I had enjoyed the records of the Beatles in the 1960s. But by 1978-’80, I had begun to discover much more substantial and rewarding music from the Big Band era of the 1930s-‘40s.

When Americans were struggling through the 1930s and then involved in a war for four years, they created charming, beautiful, uplifting songs like:

“Thinking of You”

“Once in a While”

“Deep Purple”

“Moonlight Serenade”

“At Last”

“In the Blue of Evening”

“American Patrol”

“People Like You and Me”

“There Are Such Things”

“On the Street of Dreams”

“I’ll Be Seeing You”

and “We Mustn’t Say Goodbye”

Today, when Americans live in the midst of unprecedented material comfort and excess, they create witless, raucous, ugly, vulgar noise and call it music.

The twelve songs I listed above embodied moral and esthetic restraint as well as musical and lyrical charm. To borrow an observation Lawrence Auster made when writing in 2008 about George M. Cohan’s “Over There”: The music represented by songs like these has “a sweetness, innocence, confidence, and happiness that is inconceivable in the culture of the last several decades and marks it of another era. This is the way America used to be….” [ “Over There”, View from the Right, June 28, 2008 ] Indeed it is. Men like my father and Eddy Howard and Buddy Moreno could testify to that.

The noise called rock and rap “music” is a calculated assault on such things. Merely by agreeing to place the latter in the same category with the former, under the general heading of “Music”, Americans become victims of an intellectual-philosophical swindle that works entirely to the advantage of their greatest enemies.

Fahey’s Bar closed around 1990, a Catholic retirement home across the street was abandoned years ago, a popular restaurant-cafeteria on another corner was torn down to make way for a lovely parking lot, and a hundred-year-old hotel a block away has been boarded up for ten years.

In its heyday, patriotism was in the air at the Casa Loma Ballroom and the neighborhood around it. Today, storefronts along that street are occupied by tattoo shops, trendy bars, and agitators for socialism, communism, and anarchism.

Eddy Howard died in 1963 at age 48.

Buddy Moreno lived more than twice that long; he died last year at age 103.

Such men and their kind of music come from a time and a frame of mind that are now vanished; a time when grown men and women knew how to convey emotion in words and music befitting grown-ups: Restrained and thoughtful words and music expressing a range of emotions, alternately comforting, reassuring, and uplifting. That frame of mind and sense of life are what I felt at the moment I walked past that bar and heard just a few seconds of that song.

I second what Jill Martin said about such men: We are fortunate still to remember them and enjoy their music.