House or Home

November 29, 2018

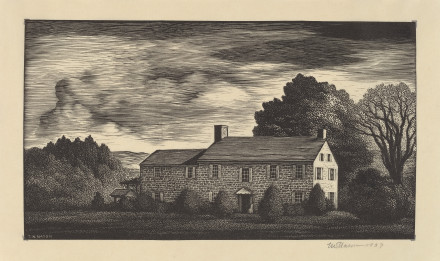

I ONCE MET a middle-aged married couple who lived in a beautiful house. It was a handsome stone house built in the late nineteenth century with a lush, well-maintained garden and very tasteful furnishings. The kitchen was a replica of a colonial kitchen except it had the most powerful and expensive appliances. The kitchen floor was covered with a rustic, brick-colored tile. The antique maple farm table in the dining room could seat at least ten people comfortably and exuded warmth. It was hard not to struggle with feelings of envy when visiting this house.

One day, the husband turned to the wife — they had no children, but one much-loved dog — and said to her, in all seriousness and with a grave expression of contempt on his face,

“You don’t interest me anymore.”

The wife was a frightfully intelligent and accomplished woman. Very interesting in many ways, but yet she didn’t always think on her feet. She should have responded with something like,

“What’s your point? You stopped interesting me the day after we were married.”

Instead she just said, “Really?” Or something similar.

He had found somebody else who was interesting.

With those few words — cold, callous, cruel words — the legal machinery of divorce was set in motion, like a truck with bad brakes barreling down a hill. In less than a year, the beautiful house was emptied and sold. She moved to the country. He moved in with his girlfriend.

The moral to the story is obvious: A house is not always a home. Even the most beautiful house, one that outwardly speaks of entrenched and unassailable traditions, one in which the birds sing with contentment in the garden, as if there were no better place to live on earth, is not always a home. One can live in a castle and not have a home. One can live in a hovel and have a home.

You can live in modest shabbiness and find your spouse, if not always entertaining, always interesting. In fact, poverty itself is very interesting. Something is always going catastrophically wrong when you are poor. Little things become big things. Perhaps that’s why it’s harder for a rich man to get to heaven than it is for a camel to pass through the eye of a needle. He’s led to believe things will always unfold beautifully.

Build your house, but don’t forget to keep your home.

— Comments —

Gary writes:

I’m a long time reader of your blog. I’m a 73 year old man from Conroe, Texas. And a Protestant.

In your post, you mention the Biblical saying….

“Perhaps that’s why it’s harder for a rich man to get to Heaven than it is for a camel to pass through the eye of a needle.”

My niece is married to an Assyrian Christian whose father speaks Aramaic, the language that Christ spoke. He says that the saying has been mistranslated somewhere back in the past.

He says the word that has been translated as “camel” should actually be “rope” and should be written as….

“It’s harder for a rich man to get to Heaven that it is for a rope to pass through the eye of a needle.”

Makes more sense doesn’t it?

Laura writes:

Nice to meet you.

It makes more sense, especially if “rope” in this context means very thick thread, because while it is impossible for a poor camel to pass through the eye of a needle, it is not impossible for very thick thread to pass through, and we know that the rich can get to heaven.

Laura adds:

I don’t know anything about the history of this translation, and would like to know more.

Note, to those unfamiliar with the reference, we are talking about the New Testament passage in Matthew 19:23-25, in which a young man approaches Our Lord to ask Him how he can be saved.

[21]Jesus saith to him: If thou wilt be perfect, go sell what thou hast, and give to the poor, and thou shalt have treasure in heaven: and come follow me. [22] And when the young man had heard this word, he went away sad: for he had great possessions. [23] Then Jesus said to his disciples: Amen, I say to you, that a rich man shall hardly enter into the kingdom of heaven. [24] And again I say to you: It is easier for a camel to pass through the eye of a needle, than for a rich man to enter into the kingdom of heaven. [25] And when they had heard this, the disciples wondered very much, saying: Who then can be saved? [26] [Douay Rheims]

Zeno writes:

Thank you for your always interesting thoughts, which I have been following for years (since I started reading the great Lawrence Auster’s blog, which I miss very much).

This is regarding the recent discussion about the New Testament quote and whether Jesus meant “camel” or “rope”. I am far from being any kind of Biblical scholar, and I know no Aramaic, Greek or even Latin. However, it seems that there is a long debate about this question, some favoring “camel” and some “rope”.

Apparently Aramaic, like Hebrew, does not have vowels, so the same word “g-m-l” depending on the way it was pronounced could mean either “camel” or “large rope”. On the other hand, the Aramaic is not really relevant to this issue, as the new Testament was written in Koine Greek.

Unfortunately, in Koine Greek it appears that the two words are ALSO homophones: (kamelos (κάμηλος) and kamilos (κάμιλος)! Not identical, but similar. So the confusion remains.

But one point in favor of “camel” is that the word is used two other times in the New Testament meaning camel (no ambiguities), and not once meaning “rope”.

I tend to favor “camel”, as Jesus was clearly making a hyperbole, and “camel” works better because it is less believable (also He uses a similar metaphor later: “Ye blind guides, which strain at a gnat, and swallow a camel”). Of course in neither case the expression is to be taken literally. So, for me, “camel” it is.

Here is however an article about the issue with a different view.

Merry Christmas and Happy New Year!

Laura writes:

Thank you for writing and adding to the discussion.

Paul VI, Franco Zeffirelli and Monty Python… there’s a lot in that article! I haven’t read it all yet.

There is a strong case for intentional poetic hyperbole here. Would so many have remembered the passage if it referred to rope?

Jon writes:

In regards to the rich man passing through the eye of a needle, I have heard from people that Jesus is referring to low gate in Jerusalem, where the camels have to stoop low to fit under. I don’t know if it’s true, but it would be a helpful picture if it is true.

Lydia Sherman writes:

There are some comments here.

In response to the translation of the word to be either camel or thick rope. It should be stated that rope was often made out of camel hair and could be the cause of confusion in this text. My resources do in fact acknowledge the existence of a needle gate. A gate not only in Jerusalem, but often constructed in city walls of that era. It was very small and easily defended to allow after-hours entrance into the city without leaving the city open to attack.

In one of the Russian othodox churches close to the church of the Holy Sepulchre in Jerusalem there is an ancient city gate revered as “the eye of the needle”.

The interpretation that seems to make sense is this. The “Eye of the Needle” was indeed a narrow gateway into Jerusalem. Since camels were heavily loaded with goods and riders, they would need to be un-loaded in order to pass through. Therefore, the analogy is that a rich man would have to similarly unload his material possessions in order to enter heaven.

Lydia adds:

One thing I note in that verse: it is harder for a rich man to enter heaven. It does not indicate that it is impossible. So that is why I was wondering if the verse was using the eye of the needle, meaning they low entrance to the inside of a city, as a figure of speech to show how a camel had to get on its knees to get through it. A rich man would find it hard to be humble enough to get on his knees.