The Virus Industry

May 27, 2020

VISIT the Centers for Disease Control website’s weekly update on deaths from Covid-19, flu and pneumonia and you will find a glaring statistical anomaly.

For the week ending on May 21, the total for all deaths from these three diseases is reported as 136,869. The breakdown is listed as the following: 88,578 deaths from pneumonia, 6,247 from flu and 71,339.

Do the math. That brings us to a total of 166,164 — close to 30,000 more than the reported total on the same page. (Thanks to Chuck Baldwin for this find.)

How could such an obvious inconsistency be overlooked by the statisticians at the federal agency?

Easily. This would not be the first time it has played with numbers.

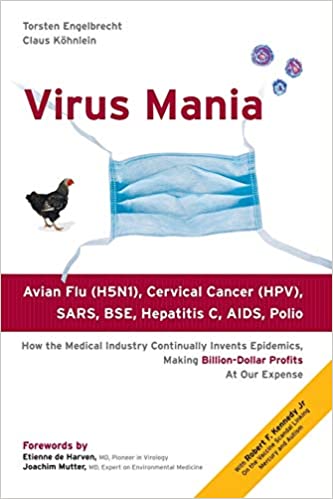

As reported in the 2007 book by journalist Torsten Engelbrecht and Claus Köhnlein, MD, Virus Mania: How the Medical Industry Continually Invents Epidemics, Making Billion-Dollar Profits at Our Expense (Trafford Publishing), during the so-called AIDS epidemic of the 1980s, the CDC produced similar weekly updates. The updates “deliberately” underestimated the percentage of drug addicts among the afflicted. Even worse, the agency declared that a constellation of symptoms was caused by a contagious agent based on what CDC officer Bruce Evatt said was “almost no evidence.”

Published 13 years ago, Virus Mania, written originally in German and translated into English by Megan Chapellas and Danielle Eagan, is highly relevant to the Covid Scandal and I am surprised — take that back, I am not surprised — that more journalists are not referring to it now. This readable, lucidly written examination of what the authors maintain is a serious tendency to overestimate the power of viruses, a tendency driven by profit motives, will help you view our latest mania in the context of modern history. The authors focus on six epidemics: AIDS, Avian Flu, SARS, Cervical Cancer (HPV), Mad Cow Disease, Hepatitis C and polio. The popular narrative of all of these is highly questionable. They also mention others along the way, including the famous Spanish Flu of 1918, reported to have killed 550,000 in the U.S. The Spanish Flu has never been proven to have been caused by a virus:

It sounds dramatic-and it was dramatic. But it’s much too hasty to assume that a virus triggered mass mortality. There are certainly no facts to support such a theory. These mass deaths occurred at the end of the First World War (July 1914 to November 1918), at a time when countless people were undernourished and under incredible stress after four years of war.

Additionally, the medications and vaccines applied in masses at that time contained highly toxic substances like heavy metals, arsenic, formaldehyde and chloroform, all of which could very likely trigger severe flu symptoms. Numerous chemicals intended for military use also moved unregulated into the public sector (agriculture, medicine) .

In 1997, a paper by Jeffery Taubenberger’s research team appeared in Science, claiming to have isolated an influenza virus (H 1N1) from a victim of the 1918 pandemic. “But before one can be certain that a pandemic virus had in fact been detected, some important questions must be asked,” writes Canadian biologist David Crowe, who analyzed the paper. The researchers had taken genetic material from the preserved lung tissue of a victim-a soldier, who died in 1918. Lung diseases were extremely typical of the Spanish flu, but it is a big leap to conclude that the many other million victims also died from the same cause. And particularly “the same virus” as Crowe points out. “We simply do not know if the majority of victims died for exactly the same reason. We also do not know if a virus can be held responsible for all mortalities, because viruses, as they’re now be described, were unknown at this time. Even if one does accept that an influenza virus was present in the soldier’s lungs, this hardly means that this virus was the killer.”

Modern civilization had been so successful at reducing or eliminating many serious diseases such as tuberculosis and diptheria (before mass vaccination) that the government considered eliminating the CDC in 1949. Instead, say the Engelbrecht and Köhnlein, the agency “went on an arduous search for viruses to justify “a very lucrative industry” of largely pharmaceutical interventions. The agency’s increasing visibility has been aided by the enormous trust placed in it by the public, in turn caused by a social trend of idolizing the wonders of medicine.

Modern medicine has tended to look for single causes to diseases. A single cause aids in the marketing of a single cure.

Things are often more complicated.

Why not suppose that a virus, or what we term a virus, is a symptom-i.e. a result-of a disease? Medical teaching is entrenched in [Louis] Pasteur and [Robert] Koch’s picture of the enemy, and has neglected to pursue the thought that the body’s cells could produce a virus on its own accord, for instance as a reaction to stress factors. The experts discovered this a long time ago, and speak of “endogenous viruses” — particles that form inside the body by the cells themselves. In this context, the research work of geneticist Barbara McClintock is a milestone.

In her Nobel Prize paper from 1983, she reports that the genetic material of living beings can constantly alter, by being hit by “shocks.” These shocks can be toxins, but also other materials that produced stress in the test-tube.110 This in turn can lead to the formation of new genetic sequences, which were unverifiable (in vivo and in vitro) before. Long ago, scientists observed that toxins in the body could produce physiological reactions, yet current medicine sees this only from the perspective of exogenous viruses.

In 1954, the scientist Ralph Scobey reported in the journal Archives of Pediatrics, that herpes simplex had developed after the injection of vaccines, the drinking of milk or the ingestion of certain foodstuffs; while herpes zoster (shingles) arose after ingestion or injection of heavy metals like arsenic and bismuth or alcohol.

It is also conceivable that toxic drugs like poppers, recreational drugs commonly used by homosexuals, or immunosuppressive medications like antibiotics and antivirals could trigger what is called oxidative stress. This means that the blood’s ability to transport oxygen, so important for the life and survival of cells, is compromised. Simultaneously, nitric oxides are produced, which can severely damage cells. As a result, antibody production is “stirred up,” which in turn causes the antibody tests to come out positive. Also, new genetic sequences are generated through this, which are then picked up by the PCR tests112 113-all this, mind you, without a pathogenic virus that attacks from outside.

But prevailing medicine condemns such thoughts as heresy.

[Part II of this review will appear tomorrow.]