Pastel Days In Texas

September 7, 2020

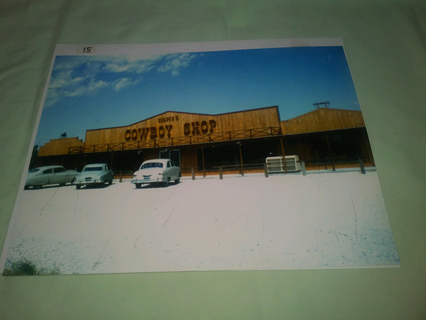

Kemper’s “Cowboy Shop”, near Denison, Texas. My aunt and uncle’s early-1950s Ford is parked under the word “Cowboy”. June 1958.

ALAN writes:

One reason older people look back as often as they do is because they know “the sands of time” are running out and they want to remember the best moments and people in their lives before it is too late to remember anything.

In my case, that involves moments and people in the old railroad town of Denison, Texas.

In the years 1958-’62, my aunt and I exchanged dozens of letters. At ages 8-12, I had an impulse to write to her and my uncle every week or so, doubtless partly because I was an only child, but also because Aunt Rose always responded promptly to my letters with detailed, informative letters of her own. I wrote to tell them about the ordinary events in our lives, and she told me about their lives in Denison.

If I could do it all over again and get it right the second time, I would have saved all of her letters. But alas, they are long gone. My mother was not a saver, and I was too young to understand what those letters would mean many decades later.

The last letter I received from Aunt Rose was in 1967. A year or so later, they moved back to St. Louis after Uncle Lawrence retired from his job with the Katy Railroad. I remember that they were with us in our living room on Christmas Eve night in 1968 when we listened to astronaut Frank Borman reading a passage from the Bible during the flight of Apollo 8.

When walking through a Catholic cemetery, I often pause at the monument bearing their names and the years of their lives. I stand there on summer days and glance toward the rolling green hills in the cemetery as I recall similar summer days at their home in Denison in the years 1958-’63, remembering how kind they were to their young nephew, and acutely aware of how much I owed to them but never paid them.

My aunt and uncle were two of the kindest, most gentle people I ever knew. They were lifelong Catholics. Their marriage lasted a lifetime. They had no children. The earliest pictures I have in which they appear are from the summer of 1927 when they visited my uncle’s Aunt Anna Rose and her husband Frank at their two-story, white-frame house in the small coal-mining town of Pocahontas, Illinois.

My uncle worked for the Missouri-Kansas-Texas Railroad in an office in the huge Railway Exchange Building in downtown St. Louis (now abandoned and lifeless).

My aunt was fifteen years older than my mother. They were the closest of sisters-in-law for seventy years. In those pictures from 1927, she was of normal height and weight. In the years when I knew her best, she was overweight. She lived 97 years.

Her friends included several Catholic nuns. In the 1980s, she was grateful for a book I managed to find for her about the history of the Sisters of the Blessed Virgin Mary.

It was not choice but circumstance that impelled them to leave St. Louis and move to Texas in 1957, when I was seven years old. The Katy Railroad abruptly moved its offices to Denison and advised its employees to do likewise if they wanted to keep their jobs. My aunt and uncle did not want to move to Texas, but it was a powerful incentive, so they did.

For a few weeks in the summers of 1958-’59, my mother and I visited them at their home in Denison. We got there and back by passenger trains. Those were among the happiest days I have ever known.

It is the ordinariness and orderliness of those days that linger in my memory. There was nothing extraordinary, “exciting”, fast, or loud. It was all so peaceful there. My aunt and uncle were as far as you can get from fast folk.

They bought a home on a residential street that was not paved, in the cotton mill district of Denison. It had a spacious living room, two bedrooms, and kitchen. Their mailbox was on a post at the end of the gravel driveway. There was a carport but no basement. The back yard was large but had only one or two small trees. There was no “home security” sign on their front lawn or those of other homes.

Among my favorite memories are these:

The deliberate pace of life. I never saw Aunt Rose in a hurry. I never heard her raise her voice. She and my uncle always spoke in a civil tone. Self-composure was the essence of their character. Moderation and modesty were key elements in their sense of life. Anything in the way of excess or profanity in their home or their lives was utterly unimaginable. The excess and profanity celebrated and encouraged by Americans today would have been unimaginable to them.

Eating breakfast and supper at their kitchen table, in a corner of the kitchen bordered by a wall whose opposite side had shelves of knickknacks. They included sets of salt-and-pepper shakers, three Kewpie dolls, and two figurines of nuns in black habits. On top of a ledge there was a lamp with a scene of a waterfall on its revolving lampshade. On a table in her living room, Aunt Rose kept two framed cameo portraits of her parents.

Riding with Aunt Rose as she drove us to a Piggly Wiggly market to help her do the weekly shopping. The ride back home was especially pleasant, along a street flanked by trees and railroad tracks.

Balmy evenings when we drove to an American Legion or VFW hall to play bingo. I could handle one or two cards, but I saw some people with six or eight bingo cards on the table in front of them. Numerous games were played, refreshments were available, and we thoroughly enjoyed such evenings. In 2015, hundreds of people showed up for the last night of bingo at the VFW hall in Denison. It closed after 82 years because of declining membership. I imagine it was the same building where we played bingo in 1958.

Days when Aunt Rose drove us to Kemper’s “Cowboy Shop”, on a highway between Denison and Sherman, Texas. How I loved going into the Cowboy Shop. The cool, dark interior was a welcome respite from the sun and heat of a Texas day in June. And there was the wonderful scent of leather goods. It was a big store with western-style clothing, gifts, and souvenirs. The entire layout met my approval because, by age eight, I had helped to tame the Old West with my TV cowboy heroes Hopalong Cassidy, Roy Rogers, and The Cisco Kid. My mother bought a butter dish, a creamer, and a sugar bowl and kept them in her china cabinet for the rest of her life—reminders of those indescribably happy days with my aunt and uncle.

The afternoons when Uncle Lawrence drove us to Lake Texoma, near Durant, Oklahoma. He drove across a long, long bridge over the lake, and fishermen were sitting on both sides of the bridge. Our destination was the restaurant at the Lake Texoma Lodge. In 1958, you could stay overnight at the Lodge for five dollars.

Going downtown with Aunt Rose, where she parked her car at a 45-degree angle to the sidewalk. There were two dime stores on Main Street: J.J. Newberry and S.H. Kress. One day in May 1959, we walked into one of them. While she and my mother shopped for whatever it was they were looking for, I managed to find a few nickel packs of Topps baseball cards, each containing a slab of pink bubblegum.

(No one who remembers Topps baseball cards from the 1950s could possibly forget the pink bubblegum. My classmates and I accumulated more than we ever wanted. It was a byproduct of our passion for baseball cards. Many years afterward, I would have nightmares about pink bubblegum. A surplus of such bubblegum had to be stored somewhere, so I stored mine in a cigar box. As the days and weeks rolled on, the slabs of pink bubblegum aged and acquired a texture similar to that of adamantine steel. To try to chew it at that point would be to rearrange my teeth. I imagined the U.S. Air Force could induce enemy villages to surrender by dropping box-loads of ossified pink bubblegum in lieu of bombs.)

Visiting with some of their friends: Dorothy and Sal and their daughter Marianne, who was my age. Her father probably worked for the Katy Railroad, too. One evening after the bingo games, we stopped at their house for an hour or so. While the grownups talked inside, Marianne and I went outside to sit in the glider swing on their front porch and enjoy the stillness and darkness of a Texas night, across from the city park.

Other friends of theirs were Mildred and Bill, a middle-aged married couple, about whom I can remember absolutely nothing except that Mildred had a bad case of arthritis. I imagine Bill may have been another of my uncle’s railroad co-workers or acquaintances. They accompanied us on our visit to Lake Texoma Lodge in 1958.

Alan with his aunt and uncle and their friends Mildred and Bill, at Lake Texoma Lodge, June 1958. [Photographs by Alan’s mother, with thanks to Agi. ]

And then there was Martha, a housewife and friend who lived next door and had a young daughter named Andrea who was as blond and fair-complexioned and soft-spoken and lovable as little girls come. She would wander over to visit Rose and was delighted when my aunt offered her a slice of cake. One day we played croquet in the back yard. It was quite a challenge for Andrea because her croquet mallet was bigger than she was. When she was seven, she typed a short letter to me and signed it, “love, little Andrea”.

“Watching TV” was not something we did. The only time Aunt Rose ever turned on her television set, in a corner of the living room, was in late evening to hear the local news and weather forecast. I remember her talking about how the heat of summer days was interrupted occasionally by powerful storms called “Texas Northerners” (if I recall correctly). On some such evenings, Uncle Lawrence sat beside me on the couch and scratched my back in a repetitive and soothing up-and-down motion as I sat there without a care in the world and gazed out through the screen door at the darkness and mystery of a Texas night.

In 1958, they had an early-1950s model Ford. As it accelerated, it had a certain characteristic sound, neither loud nor disagreeable. An air conditioned automobile was unimaginable to us. Push-button windows and doors were unimaginable. We always rolled the windows down to get the advantage of the breeze. There were no screeching “auto alarms” or cars that beeped or talked.

The typewriter. Aunt Rose was kind enough to allow me, at age eight, to try to figure out how to use her typewriter. It was a large, black, Royal manual typewriter. Sitting at her typing table, I managed to figure it out at least well enough to type notes on three postcards that I sent to my father back in St. Louis and that he kept for the rest of his life.

My aunt and uncle came back to St. Louis to visit their families each year at Christmas. Sometimes my mother and I accompanied them to Union Station in downtown St. Louis where we said goodbyes as they boarded a train to take them back to Denison. I remember standing there in the concourse of that giant train station when there were still crowds of people arriving or departing. I remember the feeling of anticipation as we waited for their train to arrive, and then the feeling of sadness as we bid them farewell a week or so later. To a ten-year-old boy, it was always a sweet but sad parting, knowing that we might not see them again for a year, and to a boy of that age, “a year” seemed forever.

Their home was painted pastel green and yellow. That was consistent with their sense of life: Nothing too loud or bright or brash. And I recall the pastel blue ambiance of early evenings when, wearing my pastel blue shirt and blue trousers and the bolo tie my mother bought for me at the Cowboy Shop, it was so pleasant to be outdoors after the bright, white heat of the typical summer day.

In the years 1962-’64, we lived next door to Mrs. H. She was a widow and lived alone. Every so often my mother would walk over there with a plate of cookies for her and to share the latest news from my aunt and uncle in Texas. At that time, it was not clear to me what the connection may have been between them and Mrs. H. Only many years later, when all of them were gone, did I discover that Mrs. H’s husband had worked for the Terminal Railroad Association in St. Louis. Then it became clear: They must have met and become friends by virtue of both men working for the railroads. (The TRRA once had ten thousand employees.)

Those are among the memories uppermost in my awareness when I stand at their gravesite, filled with gratitude to them and self-contempt for having failed to express that gratitude to them in the years when they would have appreciated it.

Last winter I received a note from one of Rose’s nephews after I sent him a photograph showing ten people (including him, Rose, Lawrence, and me) standing outside his parents’ home one day in 1958. He and I are the only survivors from that day, he noted.

That is why older people look back: Because they know it is later than you think.