A Hero’s Testimony on Women Soldiers

August 31, 2011

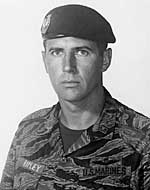

COL. JOHN W. RIPLEY of the U.S. Marines Corps was famous for his acts of bravery in the Viet Nam War. The story of Ripley’s efforts to blow up a bridge under enemy fire is legendary.

In 1992, Ripley, who died in 2008, testified before the Presidential Commission on the Assignment of Women in the Armed Forces. His testimony, posted in its entirety at the website Tradition, Family and Property, is worth reading in light of a Congressional committee’s recommendation earlier this year that all restrictions on women in combat roles be lifted.

Here are some excerpts:

I feel I have a basis upon which to comment, and I would like to read this statement: First of all, this subject should not be argued from the standpoint of gender differences. It should not be argued from the standpoint of female rights or even desires.

As important as these issues are, I think they pale in the light of the protection of femininity, motherhood, and what we have come to appreciate in Western culture as the graceful conduct of women.

We simply do not want our women to fight. We simply do not want them to be subjected to the indescribable, unless you have been there, the horrors of the battlefield.

The oft-intoned surveys that we have heard have yet to show you even a reasonable minority of women who feel that they belong in combat units. Survey after survey and question after question, ad nauseam, is answered with the overwhelming majority, around 97 percent, with “No, I do not want to be in a combat unit. There is no purpose for me being there,” and the only purpose which has been stated, as we know, is for that pathetically few who strive to gain higher command and feel that they must have served in a combat unit to achieve command, or perhaps higher rank.

The issue then becomes, “I want to be in a combat unit or to serve in that unit, to serve in combat, to qualify myself for promotion,” and this, I must tell you, is the worst possible reason, because it is self-serving. It is self-aggrandizing. The only purpose is to further the interest of the individual, as opposed to improving the unit.

Now, combat Marines will tell you that any leader, junior or senior, who focuses on himself, as opposed to the good of the unit, is completely worthless as a leader and he will never be followed willingly, and he will never gain the respect of his Marines.

Combat Marines will also tell you that they distrust any leader who puts his own wellbeing and his own ambition ahead of the mission of the unit, or the good of the unit. And that, ladies and gentlemen, is precisely what is happening here. These extraordinarily few would-be generals are saying, “It is more important for me to be in a combat unit, so that, I may profit from that and become promoted than it is for the unit to be combat effective, combat ready, and successful in combat.” And that is precisely what they are saying. That’s exactly what this issue is. (It comes down to, “My ambition, my personal needs, are greater than the effectiveness of the unit or the wellbeing and the welfare of my Marines.”)

[…]

I cannot comment to you accurately, or even with experience, on whether a woman would be an effective pilot in combat, never having been a pilot myself. I will tell you at the same time, having been shot down in a helicopter at Khe Sanh on two consecutive days, different aircraft, that no woman could have sustained the crash of the aircraft or the physical effort necessary after the crash to evacuate myself and another 16 dead and wounded in order to remove myself from this combat necessity. No woman could have done that.

No woman remaining alive after such an event would have had the physical power to extract those killed and wounded men; the pilots and the crew, absolutely no one. To see them effectively out of this enemy sanctuary, with no friendlies around me, while I remained behind, I don’t think any of them would have done that, would have been physically able to do that, and if in fact they had chosen to do that.

It took not only brute physical strength, pulling man after man out of the aircraft and into another, it took fighting back overwhelming psychological pressure to continue this grisly work, removing legs from the cockpit, parts of other bodies, and it took overwhelming—overwhelming—effort to overcome any human’s gut visceral instinct to get on that same aircraft, rather than stay behind, as the only person, while that aircraft full of casualties left; and I did so.

Now, I won’t tell you that women do not have courage. Every single mother has courage. I will not tell you that women do not have strength. Women have strength beyond description, and certainly strength of character. I will tell you, however, that this combination of strength, courage, and the suppression of emotion that is required on a daily, perhaps hourly, basis on the battlefield is rare indeed, rare in the species, and is not normally found in the female.

[…]

I would also say that the changing of standards, the oft-used term “gender-norming,” is in fact a depreciation. You are reducing your standards. You’re not “norming” your standards; you’re lowering your standards. It’s a simple fact. If your standards were at one time, as was the case with Tom Draude and myself at the Naval Academy, to perform certain numbers of physical activities, push-ups, pull-ups, boxing, wrestling, the obstacle course, et cetera, et cetera, and then suddenly that changes, and it changes down, then you have lowered your standards. Call it what it is, you have lowered your standards.

[…]

We found out when we were told to put women in drill teams—I think this was during the Ford or the Carter Administration; I can’t remember which—that we had to remove the operating rod springs in our weapons because women could not come to inspection of arms. They couldn’t. The spring has a nine-pound release, and they couldn’t move the rifle bolt to the rear.

There are simple physical, psychological, physiological differences that would require this different standard.

Do I feel, if I infer from your question, that this is correct? No, I don’t. There are certain limitations on weapons and weapons systems that are essential; that cannot be changed. You reduce the operating rod spring, you make a weapon lighter—the M-16 is a perfect example—it becomes ineffective. We couldn’t use the bayonet on the M-16 because the barrel was so light it would bend the barrel. We have corrected that in the Marine Corps. We now have a much heavier barrel, and we increased the buffer spring tension.

A woman cannot pull the cocking handle on a 50-caliber machine gun. She cannot feed a round into the weapon. They cannot undo a hatch, as a man can; the closure grip on a simple hatch. That’s a tank hatch or a hatch in a submarine. It can’t be done without assistance. Should that be changed? Personally, I don’t think so. I think these were designed with the ergonomics and the human application at some point, considerably earlier, and we found these weapons systems to work perfectly. They are certainly rugged, and they should be.

Weapons of today are nowhere near the ruggedness of the M-1 Garand, just by way of example. That’s not to say they are not good weapons, but they are designed with this ruggedness as a factor and, as such, they are more effective. If it is necessary to change it, I think we have derogated the overall effectiveness of the weapon.

When asked where he would draw the line in assigning women, Ripley responded:

My first answer, sir, is I’ve got nothing to lose. And that isn’t meant to sound the least bit derogatory to those who perhaps do have something to lose. I have spoken very candidly my whole life, and this is an issue too important to hide behind personal concerns. It’s just too important.

And I’m not sure who gave you mixed signals, but I feel deep in my heart that anyone who has shared the experiences that I have—and I certainly am not the only one to have done that—feels virtually the same way I do; I can guarantee that—who has had ground combat at the company level for over two years.

Where I would draw the line? I would draw the line at any unit which is required by the mission and the nature of that unit to close with and to kill the enemy by close combat. That includes, in the Marine Corps, rough guess, about 75 percent of all of our combat Marines, all our Marines, and perhaps units; however you define that.

I would say nothing in a Marine division at the regimental level, or those units which are supporting those regiments, the infantry and the artillery regiment.

I would say nothing in combat support units which may find themselves in enemy areas, and that includes, by the way, truck drivers who happen to be carrying essentials from place to place.

Asked about the effects on unit cohesion, Ripley responded:

I would say to you yes, absolutely yes, the fact that the females would be in a ground combat unit, infantry battalion, the men would, without question, resent it, it would destroy cohesion, wreck the unit. It would in fact set up not just a dual standard but a grossly unfair standard, because males already accommodate females. They accommodate the fact that females must have certain differences. They must have separate and better, by the nature of them, quarters. The quarters for females are private. They have better head facilities. They have better—just many better things, separate messing facilities in the desert, separate—a lot of things. We accommodate that. We don’t necessarily dislike it, but we understand why it is necessary.

If you did that in an infantry battalion, which must, of nature, reduce itself to the lowest denominator, meaning all personnel in that battalion, officer, enlisted, staff noncommissioned officer—everyone has to do the same thing. You dig your own hole, you fetch your own chow, you deal with your own personal hygiene, you: accommodate or you take whatever—share whatever lack of resources there happen to be, they would resent the fact, over a period of time, that the females must have their portion of water or whatever. And it would take a very short period of time that this accommodation which we now do would wear very thin, and it would turn to resentment, gross resentment.

I could give examples of that.

And I would also say that the mere fact that females would be in this unit would not, so to speak, equalize certain actions. The females would never carry the radios. The females would never be sent alone on an LP at night, the most unloved job in the whole unit. The females would never be required to do the things that the males are required to do, of nature, and expected.

No female would ever walk the point; simply would not. I dare say the men would not—would feel very uncomfortable with a female on point.

No female would be required in an emergency situation to move and get another couple of cans of link (machine gun ammunition) or more grenades.

No female would ever carry the outer ring of the base plate, which we don’t even have anymore.

No female would be expected to run a landline between your unit and an outpost.

No female would be required to carry “Peter and the Wolf,” a dead Marine, which only two male Marines can do, slung on a pole, because that’s the only way you can carry them in the jungle.

No female would be required to do 90 percent of the things with which I am familiar, simply because, in many cases, men would not stand for it. They would never, never permit a woman to do the things that they do, of nature, disliking, but they know they must do it.

I can tell you that unit cohesion would be destroyed.