Pyle and Childhood

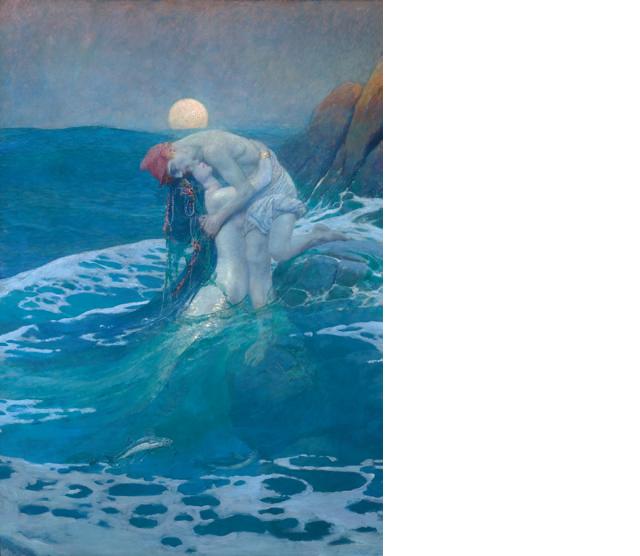

[The Mermaid, Howard Pyle; 1910. Courtesy of the Delaware Art Museum.]

THE WORKS of the great American illustrator Howard Pyle, who died 100 years ago today, are a message from the past. In the hundred years since Pyle died, the world of children has changed profoundly. It has not changed all for the worse obviously. Medical care is much better and living conditions are good. However, children no longer inhabit a mentally separate realm. It’s not just that they are exposed to sexually-explicit imagery and music. Even in run-of-the-mill commercials, as Neil Postman noted in his book The Disappearance of Childhood, children are initiated into the world of adult worries and concerns. In commercials about prescription drugs, car insurance and politics, they encounter the trivial preoccupations of adult life.

Childhood is in some ways a form of higher awareness. “What a distressing contrast there is,” said Sigmund Freud, “between the radiant intelligence of a child and the feeble mentality of the average adult.” Children know things adults can no longer fully grasp. The adult world once protected that knowledge and melded it gradually with reason, information, practical ability and wisdom. Technological change and spiritual decline have abolished that protection. It is gone in a larger cultural sense and the individual parent is left to fight against the prevailing tide.

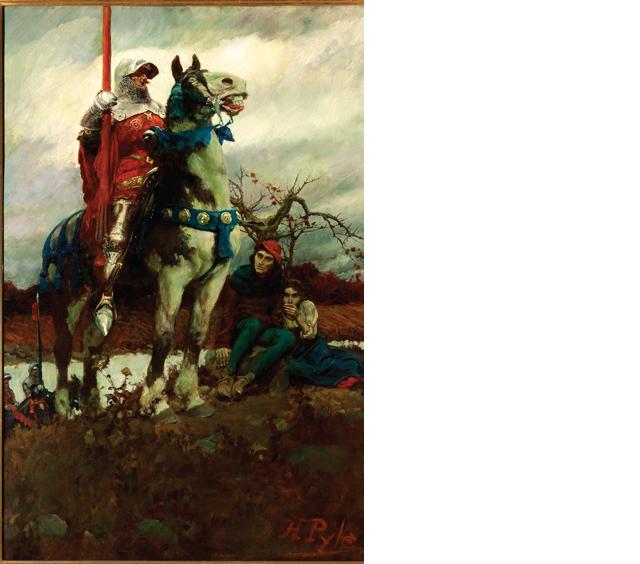

Fortunately, Howard Pyle is still alive. Just last weekend, I was at a library book sale when, as I was about to leave, I turned to a table of children’s classics. There for $2 was the 1919 edition of Howard Pyle’s novel Men of Iron. It was one of those moments of synchronicity, given that I have been writing about Pyle, that have convinced me over the years that angels have specific interests and like to interfere with our reading. Men of Iron is the fictional account of the young son of a lord during the reign of Henry IV who is unjustly accused of treason. The son, Myles Falworth, sets out to avenge his father and recover his family’s good name. Pyle’s illustration below, courtesy of the Delaware Art Museum (now staging a major retrospective of his work), depicts Henry IV on the first page of the book.

I brought the book home. It was a message from a past that still lives and from a remarkable man who had a sense of the inherent nobility of his artistic mission. Where the children’s illustrator today offers unease, confusion and escape in the occult, Pyle offered the heroic. He gave children a reason to anticipate adulthood with excitement and to perceive it for what it is, even in modern cities and office parks: a battle between the forces of darkness and the forces of light.