WTC Building 7

"DR. Niels Harrit is the Associate Professor for Chemistry at the Copenhagen University in Denmark, and a globally recognized scientist who has published various scientific papers. He was part of the scientific team which discovered nanothermite in samples of dust from the 9/11 W.T.C attacks." Watch the full interview here.

NO PASSENGER PLANE was seen at the Pentagon on 9/11. The building was hit by a missile. This is an excellent interview with April Gallup who was at the Pentagon that day. The very first police officer on the scene also said there was no plane.

THE crater was made by a military drone, seen by at least one eyewitness, and not a passenger plane. As Donald Rumsfeld said (in a slip up during a speech), Flight 93 was shot out of the sky and the debris was elsewhere. Christopher Bollyn on "the Shanksville deception:" Something incredibly ugly happened to Flight 93 over rural Pennsylvania on 9-11. A mass murder atrocity could explain why the public was deceived into thinking that a small crater was the crash site while the bodies of the victims and wreckage were actually being picked up from the real debris field hundreds of meters away in the dark woods. How many victims were there anyway? Two hundred? Why was the wreckage of Flight 93 kept hidden?

IF THE opponents of the official version of the 9/11 attacks relied on something as minor as this recording --- which could have been tampered with --- they would not have much of a case. But this is one detail in a mountain of evidence against the official story. It is a very compelling detail nevertheless. This flight attendant was likely not on the plane at the time of this call.

FROM Laurent Guyenot’s article today at Unz Review, “9/11 Was an Israeli Job: How America was neoconned into World War IV:”

Researchers who believe Israel orchestrated 9/11 cite the behavior of a group of individuals who have come to be known as the “dancing Israelis” since their arrest, though their aim was to pass as “dancing Arabs.” Dressed in ostensibly “Middle Eastern” attire, they were seen by various witnesses standing on the roof of a van parked in Jersey City, cheering and taking photos of each other with the WTC in the background, at the very moment the first plane hit the North Tower. The suspects then moved their van to another parking spot in Jersey City, where other witnesses saw them deliver the same ostentatious celebrations.

One anonymous call to the police in Jersey City, reported the same day by NBC News, mentioned “a white van, 2 or 3 guys in there. They look like Palestinians and going around a building. […] I see the guy by Newark Airport mixing some junk and he has those sheikh uniforms. […] He’s dressed like an Arab.” The police soon issued the following BOLO alert (be-on-the-look-out) for a “Vehicle possibly related to New York terrorist attack. White, 2000 Chevrolet van with New Jersey registration with ‘Urban Moving Systems’ sign on back seen at Liberty State Park, Jersey City, NJ, at the time of first impact of jetliner into World Trade Center. Three individuals with van were seen celebrating after initial impact and subsequent explosion.”

By chance, the van was intercepted around 4 pm, with five young men inside: Sivan and Paul Kurzberg, Yaron Shmuel, Oded Ellner, and Omer Marmari. Before any question was asked, the driver, Sivan Kurzberg, burst out: “We are Israelis. We are not your problem. Your problems are our problems. The Palestinians are your problem”.The Kurzberg brothers were formally identified as Mossad agents. All five officially worked for a moving company (a classic cover for espionage) named Urban Moving Systems, whose owner, Dominik Otto Suter, fled the country for Tel Aviv on September 14.[4] (more…)

ARCHITECTS AND ENGINEERS FOR 9/11 TRUTH looks at three anomalous events that occurred at the World Trade Center Towers in the months and weeks immediately preceding the attacks: There was an increase in security at the Trade Center in the two weeks before 9/11, for reasons that are unclear, which only ended the day before the attacks. Also, the fire alarm system in World Trade Center Building 7 was placed on "test condition" every morning in the seven days before the attacks and on the day of 9/11. While it was in this mode, any alarms would be ignored. WTC 7 was a massive skyscraper located just north of the Twin Towers, which mysteriously collapsed late in the afternoon of September 11. And some of the elevators in the Twin Towers were out of service in the months before the attacks, supposedly due to maintenance work or modernization.

KYLE writes:

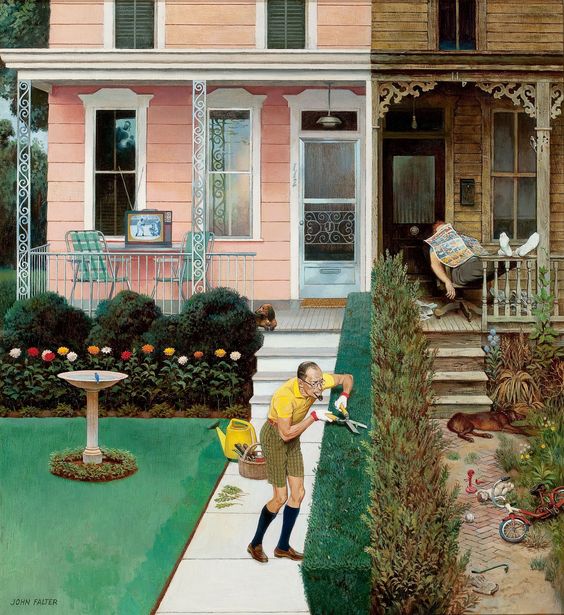

I recently drove through my old neighborhood on the way home one evening and noticed that a plurality of the houses my childhood friends grew up in, homes built in the 1970s, haven’t aged gracefully. Most of the aesthetic ornamentation of these houses has become blackened from dirt and brake dust. Window shutters, glass panes, aluminum siding, gutters, entry sidewalks, and garage doors are long overdue for a good pressure washing. Wooden deck patios are a good shove away from falling down. Flowerbeds are barren from being washed out by clogged gutters that flood the bed below and wash out the mulch. Often times garden beds are clogged with dried up leaves from the previous autumn.

Large weeds are often indistinguishable from the plants next to them. The concrete driveways we played basketball on now feature a multitude of spider-web-like cracks and in some cases, they’ve damn near been pulverized to gravel. The streets are riddled with erosion from salt that city workers pound on it during winter months. The same streets are soiled from the engine oil of parked vehicles, giving the neighborhood streets the seedy look of a Wal-Mart parking lot. (more…)

FROM Our Borders, Our Selves: America in the Age of Multiculturalism, a forthcoming book from VDare Books by the late Lawrence Auster:

We do not resist, and in most cases do not even notice, the desacralizations that surround us because they constitute the very fabric of our culture. Every culture has an organizing idea that is expressed, consciously or unconsciously, in every facet of its physical and social environment. Just as the organizing idea of medieval Europe was Christianity, and the organizing idea of nineteenth century America was democracy, so the organizing idea of our present, multicultural society is nihilism.

To characterize modern society as nihilistic may strike the reader as extreme. Nihilism is conventionally thought of as an attitude of total negation, as “a rage against creation and against civilization that will not be appeased until it has reduced them to absolute nothingness.” [Eugene Rose, Nihilism: The Root of the Revolution of the Modern Age, Fr. Seraphim Rose Foundation, Forestville, CA, 1994]. What does this frightful will to destruction have to do with our happy-go-lucky, prosperous, fun-loving country? The answer is that there are degrees and stages of nihilism short of the extreme kind described above. As Fr. Seraphim Rose writes, nihilism is entirely compatible with a “positive” attitude toward life, with enthusiasm, goals, self-esteem, creativity, and most of all with a sense of limitless freedom. What defines nihilism in all its variations is not an attitude of total negation toward everything (which, as we have said, is only the most extreme form of nihilism), but the belief that there is no absolute truth and no rational basis for determining right and wrong. In its early stages, nihilism simply denies the existence of moral truth. In its advanced stages, nihilism replaces moral truth by a new, non-moral criterion of human action–such as “power,” “vitality,” “self-fulfillment,” or “prosperity.” (more…)

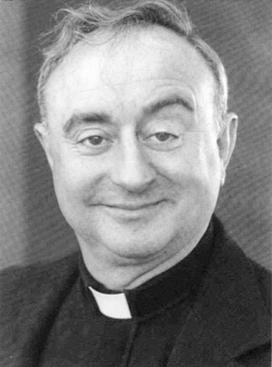

LAST MONTH, when I was away from home and not following the story, Catholic League President Bill Donohue, PH.D., wrote of the mind-blowing injustice of the grand jury report on clergy sex abuse issued by Pennsylvania Attorney General Josh Shapiro:

Importantly, in almost all cases, the accused named in the report was never afforded the right to rebut the charges. That is because the report was investigative, not evidentiary, though the report’s summary suggests that it is authoritative. It manifestly is not. (more…)

Seldom have I felt as comfortable in anyone’s presence as I did with Lynn and her family. To her, they were probably only ordinary years. But she had such a benevolent sense of life and projected such cheerfulness and optimism in her voice and her demeanor that those two years were a high point in my life.

ALAN writes:

ONE DAY last March, I was looking for a newspaper death notice. I did not find it, but I found something I was not looking for: The death notice for a man whom I had played with when he was a baby in 1963. He thus became one of the few people I have known and seen make the journey from birth to death.

It was in 1963 that I first heard the 1930s’ ballad “Deep Purple.” Missourian Jane Froman recorded it in a beautifully arranged version in the 1950s. Its tone and melody remind me of good friends of ours who are now deceased but who live in the deep purple of my memories.

On ordinary days in the spring of 1963, we became friends with a young married couple who were also our neighbors in a residential area of south St. Louis, less than a mile from where sheep grazed in fields behind a Catholic high school in the 1940s and where my great-aunt could look out the back window in her home and see a farm in the 1930s. I will call them Ken and Lynn. She was a housewife and he was a factory worker. Color slides taken by my mother show them to be a handsome couple in the prime of life. Their son was born that spring. I played with their young daughter in our backyard. (more…)

IF AMERICANS KNEW writes: Legislation to give Israel $38 billion over the next ten years is currently working its way through Congress. This is the largest military aid package in U.S. history. Yet, while Israeli media are covering the legislation, virtually no U.S. news reports have informed American taxpayers about this proposed disbursement of their tax money. The proposed military aid amounts to $23,000 per every Jewish Israeli family of four. (Aid to Israel has been on average about 7,000 times greater per capita than U.S. aid to others around the world.) The proposed aid is divided between two bills. One has already passed, but the main bill is still before Congress.

IMAGINE if Indians became a minority in Calcutta. Imagine an Arab openly celebrating the demise of Indian culture. Nuseir Yassin, known [as] Nas Daily, celebrates the demise of British culture in this video made for Facebook. Zionist Report writes: "And, if you are a non-White Goy, you should be offended by this too. Because after Europe (research the Coudenhove-Kalergi plan), your culture and race are next. In the end, if you don't know who you are, and where you come from, you have no reason to defend it... and therefore much easier to control."

TheMediaReport.com writes:

A priest washed out the mouth of a young sex assault victim with holy water? Another priest sodomized a boy with a crucifix? Another priest assaulted another kid multiple times on an airplane? 300 “predator priests”? The Church “did nothing”?

Are these sickening stories all true? No, they’re not, and we will show you explicitly in this special, two-part report.

Where does one begin to get at the truth of the recently released Pennsylvania grand jury report that has wrought breathless headlines across the globe? Here are two essential starting points: (more…)

WHEN “Monsignor” Jean François Lantheaume, former first counsellor at the “apostolic” nunciature in Washington D.C., confirmed earlier this week that he had personal knowledge that the accusations against high ranking prelates made by “Archbishop” Carlo Maria Viganò were true, he stated, “I can tell you as being the direct witness that Vigano is telling the truth: I was the direct witness! these may be the last lines I write… if I am found chopped up by a chainsaw and my body sunk in concrete, the police and the hacks will say that we have to consider the hypothesis of suicide !!!”

Perhaps Lantheaume’s statement about his own safety was simply a dark joke. But that the life of someone who would expose the homosexual network in the Vatican II Church would be in grave danger is apparently not paranoia. “Archbishop” Viganò has gone into hiding for very good reason.

In 1998, Fr. Alfred Joseph Kunz, a Catholic priest in Dane, Wisconsin, near Madison, was murdered in his rectory. No one has ever been arrested for the crime, though police say they have a suspect and those who knew Fr. Kunz have their own theories. From a report by the Dane County Sheriff’s Office (warning: this contains some graphic details and is not for those with delicate sensibilities):

“On March 4, 1998, at 7:00 a.m., the body of Fr. Alfred J. Kunz, DOB 4/15/30, was found in the hallway of St. Michael School. The school is in the Village of Dane, population approximately 600, located in rural Dane County 5 miles northwest of Madison, Wis., the state capital. (more…)