The Vatican and the Leftist Nuns

DON VINCENZO writes:

In January, 2009, the Vatican announced that an Apostolic Visitation would be made to inquire about the state of “women religious” in the U.S. What this generally means is that Vatican clerics or their representatives are directed by members of papal “dicastries” or departments to investigate charges of serious and on-going irregularities in any Catholic organizational structure. The Vatican’s rationale for this particular visit was that for decades the traditional idea of “sisters religious” (the term “nun” is usually applied only to cloistered sisters, but often the words are used interchangeably) were arbitrarily discarding their religious duties for what they called their “social ministry.”

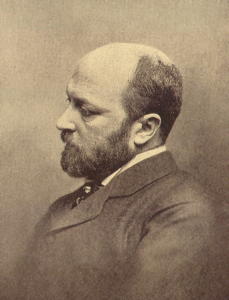

Two months after the announcement, Sister (Sr.) Sandra M. Schneiders (center photo), Professor of New Testament Studies and Christ Spirituality at the Jesuit School in Berkeley, California, in a comment to The National Catholic Reporter said that: Nuns should receive the representative of Rome politely and kindly for what they are, uninvited guests, who should be received in the parlor, but not given the run of the house.

Welcome to the new world of women religious! (more…)