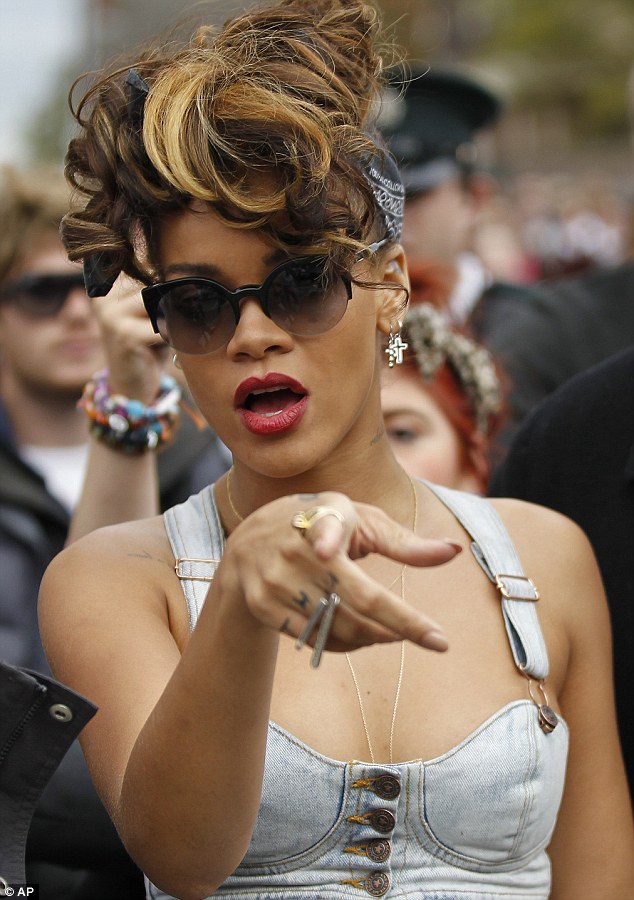

“I Decided Not to Have Children for Environmental Reasons”

THE WESTERN educated woman is so afraid of having children – so afraid of what it might require of her, so afraid of no longer breathing, thinking, and acting like a man, so afraid of losing friendships based on her status as careerist – that she reaches in her desperation for all kinds of popular superstitions to justify her psychological malformation.

Here is one of the most extreme examples. Lisa Hymas, writing in The Guardian, says she is not having children because of the effect they may have on the environment. To Hymas, human beings – not Third World human beings, but white Americans – are engaged in nothing more than environmental plunder. She writes: (more…)