Alexander Graham Bell and Mabel Hubbard

May 25, 2010

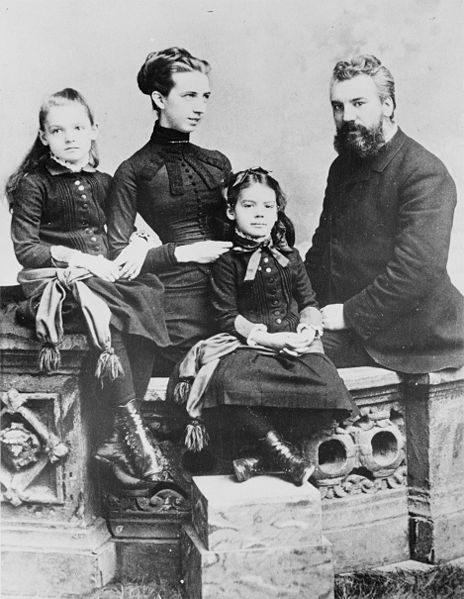

Alexander Graham Bell, Mabel Bell and their children

IN MARCH 1876, after more than a year of sleeplessness, harried experimentation and a neck and neck race with a competitor, Alexander Graham Bell filed the U.S. patent for the first working model of the telephone. It was the culmination of intense and varied interest by three generations of Bells in projection of the human voice.

On July 9, 1877, the Bell Telephone Company was officially inaugurated and a new era in modern communications began. Two days later, a new era in Bell’s personal life began when he married nineteen-year-old Mabel Hubbard in the parlor of her parents’ home on Brattle Street in Cambridge. It was the first time Tom Watson, Bell’s famous assistant, wore white gloves. Bell gave his wife 1,497 shares in the telephone company as a wedding gift. The Bells’ marriage lasted for forty-five years and in that time, Mabel never once used a telephone herself. She was completely deaf.

As part of my series “Famous Couples,” I look at one of the more interesting couples in the history of modern invention.

The first Alexander Bell, the inventor’s grandfather, was born in St. Andrews, Scotland in 1790 and became an actor and then an elocution instructor and private tutor. He was not lucky in marriage. His wife, Elizabeth Baird, who was seven years older, had an affair with an instructor at the Dundee Academy. The couple was seen together in a house of ill repute in Edinburgh, but the whole town of Dundee, except for Bell, was aware of what was going on. The subsequent divorce trial severely damaged Bell’s reputation and nearly ruined his finances. He recovered, remarried and became a celebrated teacher of elocution in London, an inspiration for Professor Henry Higgins in George Bernard Shaw’s play Pygmalion, and author of The Practical Elocutionist.

His son, Melville, also went into elocution and became an expert in speech physiology. He devised a system known as Visible Speech, in which a symbol was developed for every sound the human mouth could produce. It made it possible to transcribe any language into “visible speech” and teach pronunciation, even to the deaf. His book, The Standard Elocutionist, was a big seller in the United States, selling 250,000 copies.

Melville had better luck with marriage. Robert Bruce, in his biography Bell: Alexander Graham Bell and The Conquest of Solitude, wrote that Eliza Symonds was 34 and a woman of no great beauty when Melville met her. She was so deaf she could only hear out of a speaking tube. It seemed she was well on her way to becoming a spinster, but Bell was charmed by her cultivated mind and sweet disposition. They were married in 1844. She turned out to be a remarkable wife and mother.

Eliza is pictured years later on an enormous velocipede, a chariot-like bicycle that Alexander and his two brothers pedaled around the streets of Edinburgh. Eliza Bell was especially attuned to her three sons, Meville, Edward and Alexander, whom she taught at home until they were about ten, allowing them to roam and get into trouble. They were mischievous and famous for bizarre manipulations of sound, such as when they taught a dog to speak and made a machine that could cry like a baby. Early on, they were taken up with invention, and developed a contraption for removing the chaff from wheat.

The two brothers died in early adulthood of tuberculosis.

As a young man, Aleck Bell took his father’s interest in speech in a new direction and became a teacher of the deaf, a lifelong passion that he always maintained was the vocation he cared for more than his inventions. How much his own mother’s deafness was an inspiration for his interest is unclear. The family moved to North America after the death of his two brothers and Aleck became a teacher in Boston. He also taught at the Clarke School for the Deaf in Northampton, Massachusetts. He wrote to his parents:

It makes my very heart ache to see the difficulties the little children have to contend with on account of the prejudice of their teachers. You know that here all communication is strictly with the mouth… and just fancy little children who have no idea of speech being made dependent on lip reading for almost every idea that enters their heads. Of course their mental development is slow. It is a wonder to me that they progress at all.

At the same time, he was working on a machine that could transmit multiple telegraphs simultaneously. He also began to explore the use of electromagnetism to transmit human speech and sound waves. He returned to Boston to teach and one of his private students was 15-year-old Mabel Hubbard. She was beautiful, accomplished and ten years younger than Bell. She had gone deaf at the age of five after a bout of scarlet fever. Her father was a patent attorney who was interested both in Bell’s work with the deaf and his efforts with multiple telegraphs. She said of her new teacher that he was “so quick, so enthusiastic, so compelling, I had whether I would or no to follow all he said and tax my brains to respond as he desired.”

Mabel could read lips and could speak, but her speech was unclear. Her teacher’s interest in her quickly developed. Courtship was entirely different in the late 1800s, as we all know, but just how different it was, especially for the upper classes, is shocking. Alec (he began to spell his name this way at Mabel’s request) first confessed his infatuation to Mabel’s mother when she was seventeen. She asked him to not tell Mabel for at least a year because she was young and impressionable. He agreed.

Bell’s experiments at that time included a phonautograph, made from a dead man’s ear. The phonautograph was invented by Leon Scott, and it took the “autograph” of speech. A membrane vibrated in response to speech and a reed translated the vibrations into written patterns on glass. The deaf could compare their spoken words with the written record in an effort to speak clearly. This led Bell to the idea of a vibrating electric current that picked up speech the way the phonoautograph’s reed did. This would lead through numerous variations to the development of a crudely working telephone in June 1875. He wrote to Mabel’s father that month that he would have “an instrument modeled after the human ear, by means of which I hope tomorrow (But I must confess with fear and partial distrust) to transmit a vocal sound… I am like a man in a fog who is sure of his latitude and longitude. I know that I am close to the land for which I am bound and when the fog lifts I shall see it right before me.”

Bell agreed to not speak to Mabel about romance for a full year but was not able to keep his vow for the entire time. When he disclosed his interest, Mabel was flattered, but not romantically interested in him. He wrote to her in the summer of 1875:

“It is for you to say whether you will see me or not. You do not know – you cannot guess how much I love you… I want you to know me better before you dislike me … Tell me frankly all that there is in me that you dislike and that I can alter .. I wish to amend my life for you.”

She wrote to him:

“Perhaps it is best we should not meet awhile now, and that when we do meet we should not speak of love. It is too sacred and delicate a subject to be talked about much and till I know what it means myself I cannot sympathize with the feeling. Only if you ever need my friendly help and sympathy it is yours.”

Three months later she changed her mind, partly through her mother’s urging, and they became engaged on her eighteenth birthday. From then on, she wrote with great enthusiasm of his charms. It would be a year and a half until they married as he worked to finish his invention and make it ready for commercial use. “The telephone is mixed up in a curious way with my thoughts of you,” he wrote to Mabel. He wanted to earn enough money so that he could live in such a way to

take the hardships off life and leave me free to follow out the ideas that interest me most. Of one thing I become sure every day – that my interest in the Deaf is to be life-long with me. I see so much to be done and so few to do it – so few qualified to do it.I shall never leave this work and you must settle down t the conviction that whatever successes I may meet with in life – pecuniarily or otherwise your husband will always be known as a teacher of deaf mutes – or interested in them.

Mabel once accused him of taking an impersonal interest in the deaf, seeing them as his “cases,” but this was obviously untrue.

With the formation of the Bell Telephone Company, significant earnings were not initially forthcoming for the inventor. He and his wife lived off income from his lectures. The company was forced to defend itself against 600 lawsuits challenging Bell’s patents. In 1879 Western Union officially acknowledged Bell’s claims to the invention in a patent infringement suit against the telegraph company, and the value of the Bell’s shares soared. With this and the leasing of telephones, the Bells became wealthy, with a staff of forty in two homes in Washington, D.C. and a large estate in Nova Scotia. They had two daughters; two sons died in infancy.

It was a long and prosperous marriage between two profoundly different people. Bell, who became portly over the years and had a full, white, patriarchal beard, liked solitude and preferred to work at night, until about 4 a.m. This was unnerving to her. It was the one thing that apparently stood between them more than any other. Mabel apparently assumed he was not working much when he was up late, a strange concern considering his prodigious activity both in the field of invention in later years and his ongoing work with the deaf. Their letters to each other, written during their times apart, portray a couple that was affectionate, respectful and devoted. “I like you around,” she wrote once when he was away, “even if you are a bother sometimes. You are the mainspring of my life, and though when it is gone the other wheels go on by themselves for a time, it is very languidly and more slowly, and I want you back to give me an interest in life.”

She believed in God and he was agnostic, inclined to the liberal view in the innate goodness of man and like many scientists of his age wholly uninterested in the supernatural and theological speculations. He was an avid supporter of the female franchise and was a member of the Committee on Eugenics for the American Breeder’s Association. He suggested though never vigorously promoted the idea of selective breeding of humans. Bell was obviously influenced by Darwin and the two men were similar in that they shared an avidity for independent experimentation and love of family, though Bell was not an atheist like Darwin. They were both Victorian patriarchs.

Mabel Bell was disappointed he was not more involved with his daughters when they were young and he left at least one note to his daughter Elsie in which he expressed frustration at her lack of scientific curiosity. Both husband and wife shared an interest in early children’s education and supported the first schools established in North American by disciples of Maria Montessori. They believed children should play freely and learn intuitively, as Bell had done years before in the streets and country hills of Scotland. He told a Chicago reporter, as recounted in Conquest’s book:

The system of giving out a certain amount of work which must be carried through in a given space of time, and putting the children into orderly rows of desks and compelling thme to absorb just so much intellectual nourishment, whether they are ready for it or not, reminds me of the way, they prepare pâté de foie gras in the living geese…”

It’s tempting to think that Bell actually preferred a wife who was deaf. Mabel could listen to long explanations of Bell’s work by reading his lips. She wrote in 1895, again from Conquest:

It is not uncommon occurrence for my husband to talk to me perhaps for an hour at a time of something in which he is interested. It may be on the latest geographical discoveries, Sir Robert Ball’s Story of the Sun, or the latest news from the Chinese war, some abstruse scientific problem in gravitation – everything and anything. Very rarely do I ask him to repeat.

“I shrink from any reference to my disability,” she wrote, “and won’t be seen in public with another deaf person.” This is a shocking declaration from a woman married to one of the foremost defenders of the deaf.

Bell never had a telephone in his study and preferred uninterrupted quiet. He liked silence and was an ardent lover of nature. In many ways, he wasn’t made for the age he invented, except in his good-natured belief in science. He died on the porch of Beinn Breagh, their home in Newfoundland late at night, at the age of 75. His former speech student said, “Don’t leave me.” He made the sign for “No” in her hands and then closed his eyes. Only in an age in which science is not everything can such matches be found.

*** For more on Bell, see Bruce’s biography and Alexander Graham Bell: The Life and Times of the Man who Invented the Telephone, by Gilbert Grosvenor, his great-grandson, and Morgan Wesson. The latter book is filled with interesting photographs and graphics.

Bell’s invention led to an immense industry. His company, known in the U.S. as AT&T and as Bell in Canada, still operates. The many other companies that offer home phone service are the legacy of his work.