The Home of Carl and Karin Larsson

August 2, 2012

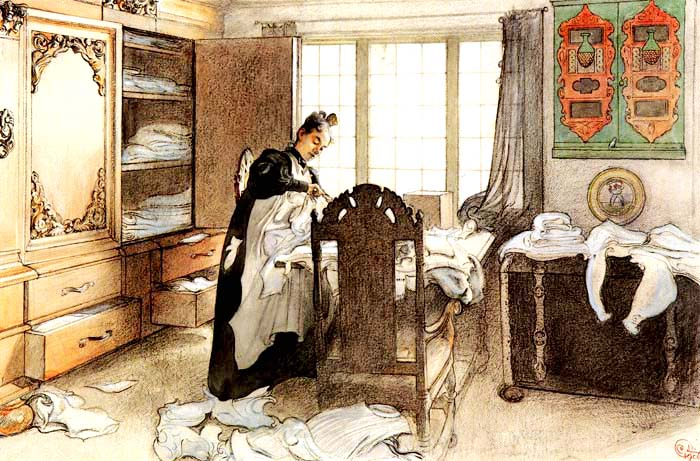

THE SWEDISH PAINTER Carl Larsson created one of the Europe’s most beloved visions of domestic harmony. Dozens of Larsson’s watercolors and paintings featured his immediate surroundings: his wife, Karin; their children, their house and the countryside near Sundborn, the village where they lived in the late nineteenth century. A son confined to a chair in punishment, the children diving into the river, two daughters getting dressed with toys scattered on the floor, the family fishing for crayfish, Karin ironing — these scenes were suffused with light, vibrant color and a deep appreciation for the enchantments of life with children. Larsson’s painting have enjoyed continuous popularity, but they have also at times been the victim of snobbery. This was to be expected. Domestic idealism is disdained in the modern world.

Nevertheless, Lilla Hyttnäs, the house in Sundborn, is one of Europe’s most popular artist’s houses and represents something of a revolution in interior decorating. While many nineteenth century interiors were somber and formal, the Larssons favored bright colors, handcrafts, and cheerful informality. Part of the Arts and Crafts Movement, they were a major inspiration for what we think of as Scandinavian design and even for the contemporary do-it-yourself movement. The house is not the kind of dwelling that would be conceived by a professional decorator. It has the organic quality that can only be the result of gradual evolution, rather than a preconceived scheme.

For those who enjoyed the discussions at this site on life in small houses, (see here, here, and here) the Larsson house, which can be viewed on the family website, may be of especial interest. The Larssons had a way of creating interesting and varied scenes in relatively small rooms.

Larsson was born in 1853, the son of a Stockholm laborer. He grew up in chaotic poverty and his family life was supposedly not happy, but a family friend spotted his talent and encouraged him. Larsson then attended the Royal Swedish Academy of Arts. He met Karin Bergoo in 1882 in Gretz-sur-Loing, France. She too was a painter and was in Gretz as part of the same Scandinavian plein air artist’s colony. They fell in love and were married.

Karin never resumed her work as a painter after they married. Thus by today’s definitions, she was not “working” and was something of a social parasite who, as Elizabeth Badinter, the French intellectual might say, was leaving her talents to wither. Karin gave birth to eight children: Suzanne, Ulf, Pontus, Lisbeth, Brita, Mats, Kersti and Esbjörn. Mats died as an infant and Ulf died at the age of 18.

In 1889, Karin’s well-to-do father gave the couple a wooden cottage which had belonged to relatives in Sundborn in the countryside of central Sweden. Carl wrote later in his famous book, Ett Hem, or A Home, of his first visit to Sundborn with Karin’s father:

The cottage stood right on a bend in the Sundborn River, just where it gets a smidgeon wider. Everything inside was spick and span, the furniture was simple, but old fashioned and robust, handed down by their parents, who had lived in the vicinity. While I was here, I experienced an indescribably delightful feeling of seclusion from the hustle and bustle of the world, which I have only experienced once before (and that was in a village in the French countryside). When my Father in law suggested buying me a small property in the same village, I declined, saying that only something resembling this little idyll would suit an artist.

A couple of years later one of the sisters died and the other did not wish to remain there alone. Father in law remembered what I had said on that occasion and gave me the cottage with everything inside it. For the next few summers radical changes were made to the cottage, it had to be exactly as I wanted it, otherwise I should not be happy there and my work would suffer as a result. Now it is finished – I believe – but before you look around be so good as to listen to my little sermon on art in the home. Others have done it better than I have, but one cannot say too much about the matter.”

They gradually expanded the cottage along the Sundborn River into a complex of buildings containing small, intimate rooms, with walls painted by Larsson and handwoven and embroidered textiles made by Karin.

According to Ulf Hard af Segerstad, author of Carl Larsson’s Home:

The method of building room after room onto an existing cottage, so that the house practically “wandered” across the lot, probably originated in England. Karin and Carl [who had traveled to England to visit Karin’s sister] knew it well; they were generally familiar with the renewing of dwellings in progress at the time on the Continent, above all in Austria. English architects such as Voysey and Ballie Scott, their Scottish colleague Macintosh, as well as the Austrians Olbrich and Hoffman were among the outstanding men of the time, in this field. They liked to use simple rectangular forms, stylized decors and a colour scale of green, rose and yellow against white.

Anna Hoffman writes:

The decoration of the house became a joint project between husband and wife. Karin made the textiles — rag rugs, slipcovers, table cloths, doorway curtains, bedclothes, etc. — and Carl painted mural decoration and arranged, carved and painted the furniture. Their home and family also became one of Carl’s favorite subjects for his paintings (Karin stopped her professional painting career when she married; they had 8 children). Thanks to Carl’s paintings of Lilla Hyttnäs, the style they created in their home became one of the crucial influences on 20th-century Scandinavian design.

The Larsson home was characterized by lightness, informality and comfort. While the typical Swede was buying expensive suites of revival-style furniture, the Larssons took their hand-me-down Gustavian furniture and mixed and matched it, slipcovering chairs and sofas. They filled their home with houseplants and colorful textiles. Instead of heavy carpets on the floor, they left the wood mostly bare and covered trafficked areas with cotton rag rugs. The motifs they used in their home were colorful, sometimes almost primitive: folk art-inflected flowers and other patterns, gingham, stripes. Some of Karin’s textiles also reflect the influence of Japanese graphic arts.

In his watercolors of Lilla Hyttnäs, Carl Larsson often included members of his family, and even the dog, living in the space. This was a home to live in, not for display — although it became an object of study by artists and designers and even social theorists, who saw in it a microcosm of family-centric social democracy.

The Larssons’ aesthetic owed a lot to the writings of William Morris, who also espoused a return to simplicity, to handcraft and to natural beauty. These qualities not only helped define the direction of Scandinavian design in the 20th century, but is still deeply influential today. Carl Larsson’s design ‘prescription’ for Swedes could serve as a contemporary rallying cry for the “undecorate” movement: “Become again simple and dignified; be awkward rather than elegant … cover everything in strong colors … let your hand naturally carve or paint on your furnishings the embellishments it can. Then you will be happy in the feeling of being yourself.”

With this beautiful home and the paintings in tribute to it, were the Larsson’s happy? Here are some interesting thoughts on this subject by Nona Hyytinen, and I quote at length because she makes some excellent points:

I have learned by reading exerpts of The World…, that after he became Sweden’s most beloved artist, Carl was attacked and deeply hurt by critics in his later years. This is not an unusual experience for anyone who achieves fame and becomes a role model. The critic that probably packed the worst sting was a former champion of his, August Strindberg. Strindberg had asserted in A Blue Book (1908), that “Carl and Karin Larsson, who at the time were the most celebrated family in Sweden, were merely putting on a show the whole time, were not revealing their true characters because the latter were diabolical and despicable, and especially that the Larsson domestic bliss, well-known throughout the kingdom, did not in reality exist — was just a lie.” (Strindberg’s assertion paraphrased byHans-Curt Koster) A more recent critic, chiming in with Strindberg, alleges that “Carl and Karin were united only by hate-love and desire for notoriety. Because Carl ‘forbade’ his wife to continue her work as an artist, she took revenge on him by forcing Carl to paint only what she had thought up.” This latter is to comment on whether the Larsson paintings of their home and family life were the creations of them both or of Carl only.

Well, as Koster admits, it’s impossible to answer such critics definitively, since the Larssons, Strindberg and the whole pre-world war era is irrevocably gone, but it strikes me as highly unlikely that the two existed in a love-hate, ambition-driven dependency.

The fact that Carl Larsson had made his personal life the subject of his paintings, thereby creating an idyll, was undoubtedly due to the fact that the books, illustrated by his artwork, were well-received and liked. We are the beneficiaries of his idyll. But even after the public taste in art changed and Larsson became for many a paradigm of bourgeois complacency, at best irrelevant as a contemporary artist, and at worst, a hypocrite, he continued to paint happy pictures of his home life.

I see Larsson as faithful to his vision. He wrote, “For life is, indeed, dreadful. Each one makes the best he can of it but if one of us sometimes has something so bearable, yes, happy,…he can not help seeing side-by-side with himself…angry..individuals….One beast torments and devours the other, one flower stifles and kills the other…For many years you have been happy to call you best friend your own and then he turns his face against you — that is hellish….That is life….But we must, in order not to despair, keep saying encouraging things to ourselves and saying: “Nice weather we’re having today!‘

Larsson consciously made himself the apostle of domestic happiness. He had had the opposite experience of childhood and family himself. ….

… I will not comment on the facts of nature, that women bear children and men don’t, which has been forever the reason women’s talents have rarely had the opportunity to be honed to the degree men’s have. This was no doubt at work in Carl and Karin’s relationship. However, I do not find it hard at all to believe in relative domestic bliss. Way back in 1994, when the movie version of Little Women, starring Winona Ryder and Christian Bale, was released, having a chance conversation with someone in a doctor’s waiting room. The (younger) woman told me she “despised the movie, because no one’s life was so sweet and cloying.” My response was only, “Ummmmmm…..” Frankly, such a wholesome family experience was completely famiiar to me, probably more banal and less story-worthy, but when I looked about myself, at my own life and that of my friends’, I didn’t find Little Women particularly unrealistic. (Louisa May Alcott had really wanted to write thrillers and gothic novels about murder and romance, not a novel extolling virtue and personal growth.) It’s certainly an edited version of Victorian life, but I think the spirit that pervades it is a completely valid human idealism.

Human idealism, a penchant for turning to the wholesome and upbuilding, is as valid as anything darker. It is a real part of the spectrum of human experience, especially if one is determined to choose it over despair and bitterness.

Many of Larsson’s works are reproduced at the website Scandinavian Treasures. A reader, Meredith, wrote the following in recommending Larsson:

It’s obvious, when looking at his work that he absolutely adored his family. Karin was also an artist, but upon marrying Carl, she threw herself into creating the home that is now considered to be one of Sweden’s national treasures (yes, that IS ironic). She is immortalized in his paintings as he saw her, forever young and beautiful.

I feel a special kinship with Karin, as I too am an artist, but have put off my “professional” work and now consider my home, husband and five children to be my special “creative work in progress.” Judging from my own experience, I seriously doubt that she felt bored or unfulfilled in her life.