From The Framework of a Christian State by Fr. Edward Cahill, S.J. (McGill and Son, 1932); pp. 42-44:

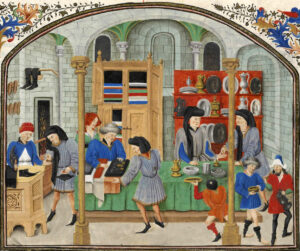

The mediaeval law of Just Price is another example of the altruistic spirit which permeated the social and economic life of the middle ages. Individuals were not permitted to use freely the property they controlled in ways that might be detrimental to the common good. They were compelled, when the needs of others required it, to place the goods they had to dispose of at the service of the public under equitable conditions. The poor and weak were protected against unfair competition, so that all might be secured a fair access to the material goods of the community.

The laws of Just Price had to be observed in wages, buying and selling and every contract of exchange; otherwise the contracted was accounted unjust and invalid in conscience, and the aggrieved party had a claim to restitution. ‘Whoever,’ writes Trithemius, a well-known fifteenth century author, ‘buys up corn, meat and wine in order to drive up their prices, and amass money at the cost of others, is, according to the laws of the Church, no better than a common criminal. In a well-government community all arbitrary raising of prices in the case of articles of food and clothing is peremptorily stopped. In times of scarcity merchants who have supplies of such commodities can be compelled to sell them at fair prices; for in every community care should be taken that all the members should be provided for, lest a small number be allowed to grow rich, and revel in luxury to the hurt and prejudice of the many.’

Contract between Christian and Non-Christian Standpoint.

In the old Roman law, just as in modern Liberal states, selfishness was assumed to be the dominating motive in every contract; and the fullest liberty was allowed to both parties to decide the price and even to over-reach each other, provided nothing was done that the law regarded as fraud. According to mediaeval teaching on the other hand, the price of a commodity was supposed to be determined by objective value alone; and could not be justly influenced by the special need or ignorance of buyer or seller.

Doctrine of the Just Price.

This doctrine, which was universally accepted in mediaeval times, is thus summarised by St. Thomas:

“It the price exceeds the value of the thing, or if the thing is worth more than the price paid, the equality which justice requires is done away with.’

The seller cannot justly extract a higher price merely on account of the special need the buyer may have of the thing, or the accidental advantage that may accrue to him form it; for in such cases he would be selling what is not his. Hence the criterion of exchange value was something intrinsic to the commodity itself, not merely competition or the higgling of the market. Hence, too, the modern distinction between value in use and value in exchange was recognized to a very limited extent.